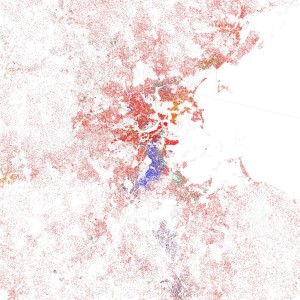

Across the country, residential segregation by race has declined slightly over the last 40 years, since the Fair Housing Act was passed, but it’s still pronounced in major metropolitan areas. Residential segregation by income, however, has been on the rise since 1970.

So say three sociologists in a journal article published this month, “Neighborhood Income composition by Household Race and Income, 1990-2009.” This one of several scholarly articles in recent years documenting the increase in socioeconomic segregation nationally.

Studies like this typically focus on urban areas, so one might wonder how much their findings apply to a demographic outlier like Vermont. Still, it’s worth considering whether some conclusions resonate here. Here’s one:

“(M)iddle-class households are typically located in neighborhoods that are more similar to those of low-income households than to those of high-income households. That is, high-income households re more segregated from middle-class and poor households than low-income households re from the middle class and the rich.”

This is consistent with an earlier study of residential segregation by income that found that “During the last four decades, the isolation of the rich has been consistently greater than the isolation of the poor.”

Why might that matter? “The increasing geographic isolation of affluent families means that a significant proportion of society’s resources are concentrated in a smaller and smaller proportion of neighborhoods.”

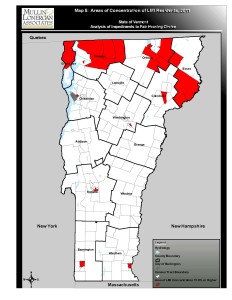

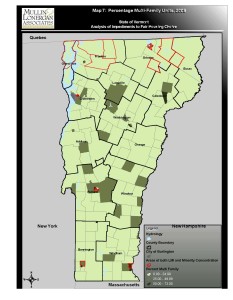

How Vermont’s neighborhood and regional compositions by income are changing is a dissertation topic waiting to be explored. The 2012 “Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice” offers a mere snapshot from the 2010 Census. Of the state’s 184 census tracts, there were 23 where at least 51 percent of the residents met the criterion for low-to-moderate income status (less than 80 percent median income). Here they are again:

Is the number of LMI districts on the rise in Vermont or not? Perhaps the upcoming state assessment, to be undertaken under HUD’s new affirmatively furthering fair housing rule, will offer some clues.