Consider Burlington times three. That’s Ann Arbor, sort of.

Ann Arbor, like Burlington, has a big student population and a big housing-affordability problem. But now all of a sudden, seemingly, it has something else that Burlington doesn’t: a rental housing glut. Thanks to a profusion of new housing, both on-campus and off, the vacancy rate is up, empty apartments are going begging at the start of another academic year, and some rents are coming down.

Let’s pause here to run the numbers: Ann Arbor’s population is 117,000; the University of Michigan’s enrollment is 43,625, or about 37 percent.

Burlington’s population is about 42,300; UVM’s enrollment is about 12,700, Champlain College’s about 2,000. So, students here comprise around 35 percent.

Ann Arbor’s rents look to be roughly in Burlington’s range. An older, four-bedroom home rents for $2,800, or $700 per bedroom, according to the Ann Arbor News.

Before the surplus in rental housing became apparent, Ann Arbor officials were talking about how to address the affordability problem. The idea of rent control was floated – as it is occasionally in Burlington – but remains impossible without legislative authorization. As things stand, thanks to a 1988 state law, Michigan’s towns and cities can’t do anything to control rent. That means inclusionary zoning is banned, too. Burlington at least has that.

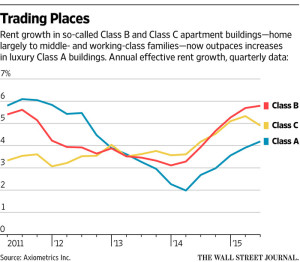

How many of Ann Arbor’s new high-rise rental units are affordable? Probably very few – developers seemingly have no financial incentive to provide any. The good news, for renters, is that some rents are dropping because of all the housing that’s been built (including graduate-student housing by the university). That’s what officials in Burlington like to imagine happening here, too: more student housing plus more private housing development alleviating the upward pressure on rents.

Sounds promising, but Ann Arbor has paid what some might consider an unsightly price: a surfeit of luxury high-rises downtown: