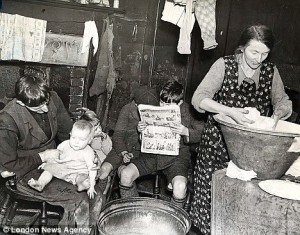

Once upon a time, believe it or not, planners of public housing in the United States believed high rises were a good thing. In the early ‘40s, we learn from J.A. Stoloff’s history of public housing, the thought high-rises “could provide a healthy, unique living environment that would contrast favorably with surrounding slum areas.”

Well, as we all know, high-rises for families didn’t work too well in the big metro areas. Two notorious examples in Chicago were Cabrini Green …

and Robert Taylor Homes…

drab, unsightly, unlivable in many ways, they unfortunately tainted the popular conception of public housing. No public-housing high-rises were built after the early ‘70s, and by the ‘90s many of these buildings were being torn down.

As it turned out, though, some public-housing high-rises did work pretty well – for elderly residents. One such example, built in 1971, is the tallest building in Vermont – 11-story Decker Towers in Burlington, operated by the Burlington Housing Authority for elderly and disabled residents:

Granted, construction of ANY public housing is passe in this country, sadly, but before you stop thinking about high-rises, look at some examples in Singapore, where public-housing high-rises are home to a majority of the population. These shots are by Peter Steinhauer, a photographer:

These photos make two things really clear: (1) High rises don’t have to be drab and dreary…

… and (2) no one should have any trouble finding the street address of these places.

The bright colors bring to mind some of the buildings in Burlington’s Old North End, many of them owned or developed by Stu McGowan …

Now that we’ve drawn your attention back to Vermont, let’s consider building height on a Vermont scale as we also consider how to add to the state’s affordable housing stock. High rises are out of the question, of course, especially in our small towns. But what about adding a third story to buildings in town centers, here and there, for family apartments? Is that such an outrageous idea? This three-story building in the photo below doesn’t look a bit out of place.