Yesterday was the due date for Burlington’s CAPER – that is, the Consolidated Annual Performance & Evaluation Report that the city has to file with HUD every year as a condition of receiving Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) and HOME funds. (HOME is a federal program that supports the rehabilitation, acquisition and construction of rental housing.)

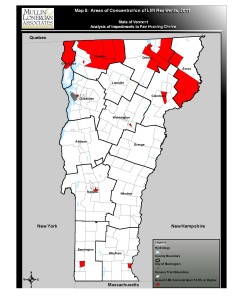

If you want to know more about the allocation of these funds, which amount to several million dollars, and about the beneficiaries, you can go to the report, which covers July 1, 2014 to June 30 , 2015. Here, we’re just going to refer to three graphics that apply to housing.

The first two may look familiar to you. They’re in Appendix A, Pages 53 and 54. Rental vacancy rates in Chittenden County have been exceedingly low for at least two decades, as shown on the first graph, and still are. That’s one reason rents are as high as they are.

The vacancy rate here here is typically below 2 percent. That’s below the “Balanced rate” of 4 percent supposedly the threshold for a healthy rental market, and its well below the rates for the Northeast and the U.S.

As for the housing wage – that is, the amount a person has to earn to be able to afford to rent an dwelling of average cost — well, no big surprises here, either. The graph on Page 25 shows four pillars, left to right, represent the costs of renting apartments: efficiency, one-bedroom, two-bedroom and three-bedroom. As you can see, a minimum-wage worker is out of luck, as is a median-wage worker who wants anything bigger than an efficiency.

By definition, you can “afford” an apartment if you spend no more than 30 percent of your income on housing. For context: According to the 2015 edition of “Out of Reach,” put out by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Vermont’s two-bedroom-apartment housing wage is $20.68 an hour, and the average wage for renters is $11.78.

OK, so how did Burlington fare for the year in its affordable housing program? It came up short, as you can see in the following table:

CR-20 – Affordable Housing 91.520(b)

Evaluation of the jurisdiction’s progress in providing affordable housing, including the number and types of families served, the number of extremely low-income, low-income, moderate-income, and middle-income persons served.

| |

One-Year Goal |

Actual |

| Number of Homeless households to be provided affordable housing units |

15 |

0 |

| Number of Non-Homeless households to be provided affordable housing units |

76 |

46 |

| Number of Special-Needs households to be provided affordable housing units |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

91 |

46 |

| |

One-Year Goal |

Actual |

| Number of households supported through Rental Assistance |

0 |

0 |

| Number of households supported through The Production of New Units |

25 |

28 |

| Number of households supported through Rehab of Existing Units |

6 |

6 |

| Number of households supported through Acquisition of Existing Units |

60 |

12 |

| Total |

91 |

46 |

Granted, a single year is a rather arbitrary term to judge and overall program, given that affordable units might well be coming on line before or after. Such is the case here, the report notes, with the prospect of the Bright Street Co-op. You can read the city’s account of its affordable housing program on Pages 24-26, where the reader is assured that:

“Ensuring the availability of a continuum of housing, for all residents of Burlington, continues to be a top priority for the City.”