We all know that no single approach will alleviate the affordable housing crisis. Government, which bears the lion’s share of the responsibility, is not fully up to the task, and as we’ve mentioned, the issue is not even getting its share of attention in public forums or political campaigns.

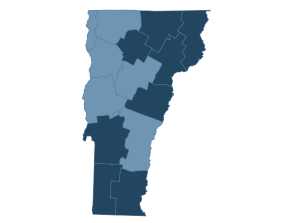

Here and there, private and nonprofit initiatives peck away at the problem. Among those initiatives is home sharing, which addresses two of Vermont’s well-known trends: a greying population that wants to be able to age in place; and unaffordable housing costs for the younger set, including the proverbial young professionals.

Home sharing matches older homeowners with younger renters willing to help out who can’t afford market rents. An apt match is a win-win, as this article in Monday’s Valley News explains.

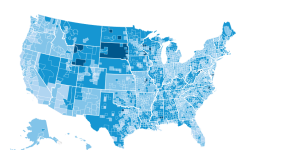

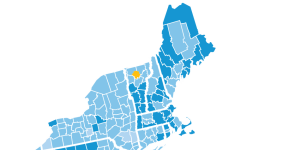

Granted, this program is a drop in the housing-unaffordability bucket, with fewer than 200 shared properties. But it’s a drop that deserves to grow, along with the post-65 population bulge that makes Vermont, by some measures, the oldest state in the country.