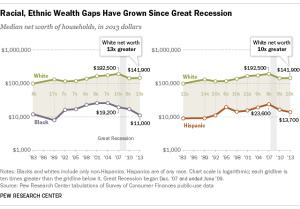

Middle-class financial struggles have occupied the public discourse for some time, but wouldn’t you know, we’re starting to hear more about housing unaffordability as a stresser for this beleaguered population segment.

The annual “State of the Nation’s Housing” report from Harvard took note this summer:

While long a condition of low-income households, cost burdens are spreading rapidly among moderate-income households. The cost-burdened share of renters with incomes in the $30,000–45,000 range rose 7 percentage points between 2003 and 2013, to 45 percent. The increase for renters earning $45,000–75,000 was almost as large at 6 percentage points, affecting one in five of these households. On average, in the ten highest-cost metros—including Boston, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco—three-quarters of renters earning $30,000–45,000 and just under half of those earning $45,000–75,000 had disproportionately high housing costs.”

Granted, much of the news about middle-class housing unaffordability is coming out of the big cities – places where “middle income” is construed to reach far above Vermont standards. For example, Cambridge, Mass., is taking steps to reserve a share of “affordable” housing in a new Kendall Square building for families with incomes in the low six figures! San Francisco is also considering measures that would expand affordable housing eligibility and help out renters in the $100,000 to $140,000 bracket. And Portland, Ore., where the “housing emergency” is apparently wide-ranging, is looking at a form of inclusionary zoning that make apartments available to people making 100 120 percent of the median income (Up to $96,875 for a family of four).

Perhaps it’s a testament to the severity of the housing crisis around the country, and/or to the fragility of the middle-income stratum, that the terms “middle class” and “subsidy” are suddenly being spoken in the same breath.

Here’s the thing: To qualify for most subsidized housing, applicants can’t earn more than 80 percent of the local median income. Where does that leave people who draw an average salary, or perhaps a little more? Perhaps in a place where they can’t readily afford housing but can’t get any help, either. How many such people there are in Vermont is unclear; plenty, no doubt.

(Note: Middle-income earners are not beneficiaries of Burlington’s inclusionary zoning ordinance, which aims to provide affordable rentals for people earning up to 65 percent of the median; and for sale, up to 75 percent.)

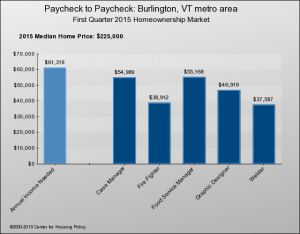

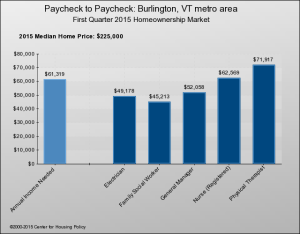

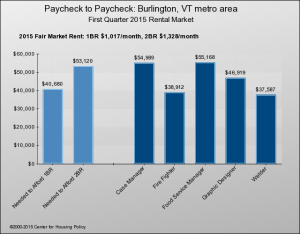

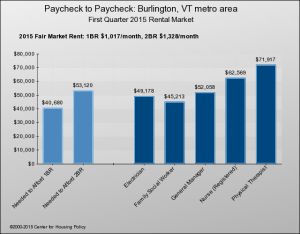

For an illustrative display of how housing costs compare to standard incomes, the National Housing Conference’s interactive “Paycheck to Paycheck” shows bar graphs for each of the nation’s metro areas – and just one in Vermont, Burlington/South Burlington. One graph compares salaries to the pay needed to afford a median-priced home; another does the same thing for 1- and 2-BR apartments at HUD’s “fair market rent.”

Below are the charts for 10 occupations that might be considered to be middle class. As you can see, eight of the 10 would be hard pressed to afford purchase of an average home in Burlington:

They do a little better in the rental market, but still, six of 10 can’t comfortably afford a two-bedroom apartment in Burlington: