Getting a head start on April in March –

Getting a head start on April in March –

Note: All the content below in this post is taken from a web site maintained by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

is taken from a web site maintained by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

In April, we come together as a community and a nation to celebrate the anniversary of the passing of the Fair Housing Act and recommit to that goal which inspired us in the aftermath of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination in 1968: to eliminate housing discrimination and create equal opportunity in every community.

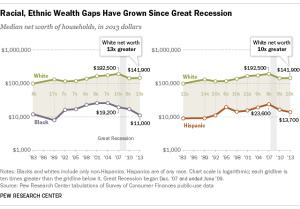

Fundamentally, fair housing means that every person can live free. This means that our communities are open and welcoming, free from housing discrimination and hostility. But this also means that each one of us, regardless of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, familial status, and disability, has access to neighborhoods of opportunity, where our children can attend quality schools, our environment allows us to be healthy, and [for us to grow] opportunities and self-sufficiency.

…commitment to fair housing is a living commitment, one that reflects the needs of America today and prepares us for a future of true integration.

History of Fair Housing –

On April 11, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which was meant as a follow-up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The 1968 act expanded on previous acts and prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, sex, (and as amended) handicap and family status. Title VIII of the Act is also known as the Fair Housing Act (of 1968).

The enactment of the federal Fair Housing Act on April 11, 1968 came only after a long and difficult journey. From 1966-1967, Congress regularly considered the fair housing bill, but failed to garner a strong enough majority for its passage. However, when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson utilized this national tragedy to urge for the bill’s speedy Congressional approval. Since the 1966 open housing marches in Chicago, Dr. King’s name had been closely associated with the fair housing legislation. President Johnson viewed the Act as a fitting memorial to the man’s life work, and wished to have the Act passed prior to Dr. King’s funeral in Atlanta.

Another significant issue during this time period was the growing casualty list from Vietnam. The deaths in Vietnam fell heaviest upon young, poor African-American and Hispanic infantrymen. However, on the home front, these men’s families could not purchase or rent homes in certain residential developments on account of their race or national origin. Specialized organizations like the NAACP, the GI Forum and the National Committee Against Discrimination In Housing lobbied hard for the Senate to pass the Fair Housing Act and remedy this inequity. Senators Edward Brooke and Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts argued deeply for the passage of this legislation. In particular, Senator Brooke, the first African-American ever to be elected to the Senate by popular vote, spoke personally of his return from World War II and inability to provide a home of his choice for his new family because of his race.

With the cities rioting after Dr. King’s assassination, and destruction mounting in every part of the United States, the words of President Johnson and Congressional leaders rang the Bell of Reason for the House of Representatives, who subsequently passed the Fair Housing Act. Without debate, the Senate followed the House in its passage of the Act, which President Johnson then signed into law.

The power to appoint the first officials administering the Act fell upon President Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon. President Nixon tapped then Governor of Michigan, George Romney, for the post of Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. While serving as Governor, Secretary Romney had successfully campaigned for ratification of a state constitutional provision that prohibited discrimination in housing. President Nixon also appointed Samuel Simmons as the first Assistant Secretary for Equal Housing Opportunity.

When April 1969 arrived, HUD could not wait to celebrate the Act’s 1st Anniversary. Within that inaugural year, HUD completed the Title VIII Field Operations Handbook, and instituted a formalized complaint process. In truly festive fashion, HUD hosted a gala event in the Grand Ballroom of New York’s Plaza Hotel. From across the nation, advocates and politicians shared in this marvelous evening, including one of the organizations that started it all — the National Committee Against Discrimination In Housing.

In subsequent years, the tradition of celebrating Fair Housing Month grew larger and larger. Governors began to issue proclamations that designated April as “Fair Housing Month,” and schools across the country sponsored poster and essay contests that focused upon fair housing issues. Regional winners from these contests often enjoyed trips to Washington, DC for events with HUD and their Congressional representatives.

Under former Secretaries James T. Lynn and Carla Hills, with the cooperation of the National Association of Homebuilders, National Association of Realtors, and the American Advertising Council these groups adopted fair housing as their theme and provided “free” billboard space throughout the nation. These large 20-foot by 14-foot billboards placed the fair housing message in neighborhoods, industrial centers, agrarian regions and urban cores. Every region also had its own celebrations, meetings, dinners, contests and radio-television shows that featured HUD, state and private fair housing experts and officials. These celebrations continue the spirit behind the original passage of the Act, and are remembered fondly by those who were there from the beginning.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development