An interesting story in the UC-Berkeley student newspaper touches on several themes of interest. Yes, it’s alien territory – high-rent California, urban beyond our rustic imagination (Alameda County alone, home to Berkeley and Oakland, has 2 ½ times the population of the entire state of Vermont).

Still, there’s resonant material here:

- A university food-service worker who can’t afford to live in the town where she works, Berkeley, and who thus must endure a long commute. She pays a mere $1,400 for a 2BR apartment in Richmond (hey, at $700 a bedroom, that’s about the going rate in Burlington!). Berkeley’s 2BR apartments average about $2,100. Here’s a shot of a Berkeley “castle.” Not so exotic, really — we can picture a building like this in St. Johnsbury or Rutland.

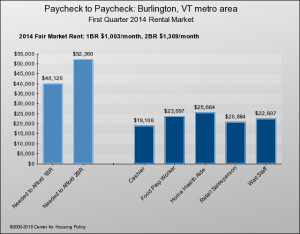

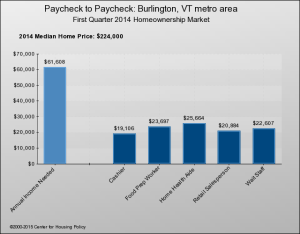

Chances are, a UC food-service worker makes a good deal more than a UVM food service worker. After all, the University of California recently raised its minimum wage to $15, more than Sodexo pays its line workers in Burlington, and the main beneficiaries were reported to be student employees, apparently because the regulars were already getting at least that much.

So, yes, the numbers are all inflated compared to our world, but the cast of characters is similar: workers who can’t find affordable housing near where they’re employed or where their kids go to school.

- Berkeley has had some form of inclusionary zoning for nearly 20 years, but it hasn’t done the trick. In fact, the affordable housing shortage has increased. This doesn’t mean inclusionary zoning is worthless. It’s an important policy tool, but it’s not salvation and in many cases produces only a small fraction of the affordable units needed. (Burlington’s total is less than 250 units over 25 years, fewer than 100 of which were rentals).

Here’s another, not-so-picturesque perspective of pricey Berkeley:

- Simply building more housing isn’t going to solve the affordability problem. So says a housing activist quoted in the stories. Yes, he’s talking about the Bay area, which apparently is pretty well-built out within its topographic limitations. Building new housing there typically means tearing down an existing building and replacing it with something taller and more costly.

We hesitate to draw the same conclusion about Burlington, which likewise is pretty well built out, but which still has plenty of room for in-fill and accessory units. Here, a surfeit of additional rental units might indeed alleviate the upward pressure on rents, but not enough, we suspect, for low-wage workers at our state university.