We begin the week with bulletins from unlikely places that nevertheless bear on what this here website is all about…

- First, an editorial out of Charleston, S.C., about a “housing affordability crisis” in a town called Mount Pleasant:

It seems that lots of people who work in Mount Pleasant (population 75,000) can’t afford to live there. (Sound familiar?) The town has something called a “workforce housing” plan, intended to encourage development of housing that people who make 80-120 percent of the area’s median income can afford, but the plan hasn’t produced much. And now, there’s talk of eliminating the plan’s density bonuses so that even less affordable housing would result.

And this is a region where about half the residents already spend more than half their income on housing. The good news, we suppose, is that the town has a workforce housing plan and density bonuses to begin with. That’s more than can be said for some communities. The challenge – in Mount Pleasant and elsewhere — is to ensure that they actually come to something.

The editorial comes to a conclusion that sounds rather familiar: “The town needs a healthy mix of residents to remain vibrant and prosperous in the future, and those residents – of all income levels – will need a place to live.”

(By the way the Post and Courier won the public-service Pulitzer this year for a series on domestic violence against women – a prize citation that the newspaper reminds us of on its masthead – so, as newspapers go, it’s fairly reputable.)

- Next up is a letter to the Salem (Mass.) News from a “Witch City” resident decrying Massachusetts’ “shameful housing demographics.”

Since 1969 Massachusetts, to its credit, has had an affordable housing program called Chapter 40B. Chapter 40B permits the overriding of local zoning bylaws to allow affordable housing development in towns where less than 10 percent of the housing stock is affordable.

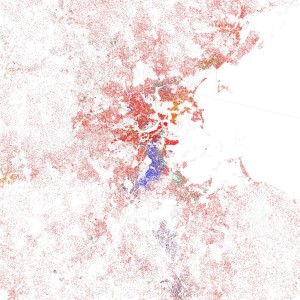

More than 50,000 units have been developed over the years, statewide. The problem noted by the letter-writer is that some recent projects have been targeted to urban areas that already have their share of affordable housing, rather than to the “leafy suburbs.” The takeaway point here is that a good measure of new affordable housing units should be located in middle-income and upper-middle income areas, not just in the same old places.

- Lastly, an update on what appears to be the longest-running fair housing case in the country.

Back in 1971, Hamtramck, Mich., was found to have violated civil rights of black residents by razing their neighborhoods as part of urban renewal. The remedy was supposed to be provision of 200 family housing units and 150 senior housing units, we learn from an Associated Press account. Well, it seems that Hamtramck still hasn’t made good, and the judge who presided over the case originally is still determined, at age 93, to see it through.

Here’s hoping that protracted case in Westchester County, N.Y., is resolved sooner.