Yesterday’s post took note of the housing burden borne by Burlington’s renters (they pay 44 percent of their income, on average, on rent/utilities). Demographically, that’s a significant burden, because renters in this city are the majority.

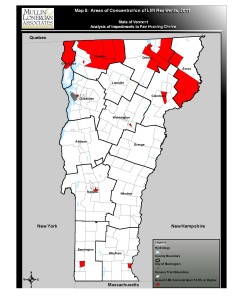

In a state where the home ownership rate is over 70 percent, about 9 points above the national average, not many other municipalities can make that claim. Only one other can, in fact: Winooski.

According to the Vermont Housing Data website, 62.2 percent of Winooski’s residents who live in occupied units are renters. In Burlington, the figure is 57 percent.

These are the only communities in the state where the renter population outnumbers homeowners. The renter-occupant figure for Vermont as a whole is 25.9 percent.

Conscientious readers may recall that Winooski scored No. 1 on the workforce housing index we introduced last month. In case you missed it, that index showed the number of subsidized housing units for every 100 in Vermont’s major employment centers. (We defined major employment centers as municipalities with 2,000 jobs or more in 2014.) Burlington came in at No. 5.

As it happens, several other employment centers that do a relatively good job of providing affordable housing also have big renter populations.

Barre City’s renter population is 48.5 percent; Rutland City’s, 42.7 percent; Brattleboro’s, 43.2 percent; St. Albans City’s, 46.9 percent; and St. Johnsbury’s, 40 percent.

Of the big suburbs surrounding Burlington/Winooski, South Burlington has the highest renter proportion (30.8 percent). The others are all below the state average: Colchester, 25.8 percent; Essex, 20.6 percent; Shelburne, 17.3 percent; and Williston, 14.9 percent. (All of these communities are “major employment centers,” by the way.)

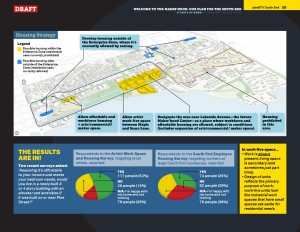

When people talk about the need for affordable housing in Vermont, they’re talking mostly about multi-family housing for renters (although, yes, efforts to promote accessory rental units, as well as single-family homes/condos for purchase, are important). So, here are a few things to keep in mind about renters in Vermont generally, as compared to homeowners:

- The median household income for a Vermont renter household ($30,943) is less than half that for the homeowner household ( $64,771).

- The housing cost burden falls more heavily on renters. Among renters:

— 52.5 percent pay more than 30 percent of their household income on housing, as compared to 32 percent of owners;

–26.4 percent pay more than half their household income on housing, as compared 12 percent of homeowners.