A while back, we introduced the workforce housing index – namely, the number of subsidized housing units for each 100 jobs in a community.

And we listed Vermont municipalities with 2,000 jobs or more — we called them “major employment centers” — with their respective indices. Winooski topped them all, followed by Barre City and Springfield.

Well, what about the rest of the state – especially the municipalities with 500 to 2,000 jobs, which we’ll call “medium employment centers”? How do they rate?

Let’s start with the municipalities that have zero subsidized units — that is, places that are fairly strong on employment opportunity but weak on housing affordability. Here they are, with their 2014 jobs from a Department Labor database in parentheses:

Cambridge (1,390 jobs in 2014), Charlotte (524), Clarendon (1,292), East Montpelier (685), Fairlee (540), Ferrisburgh (547), Highgate (616), Hyde Park (690), Jay (730 jobs in third quarter), Killington (1,735), New Haven (641), Shaftsbury (530), Stratton (529) and Thetford (621).

On the other end, the “medium employment center” with the most subsidized units per 100 workers is Brandon. Brandon had 1,374 jobs and 156 subsidized units, for a workforce housing index of 11.4 — that is, 11.4 units for every 100 workers employed in the town.

Going down the list of municipalities that had between 500 and 1,999 jobs):

Williamstown: 11.3 (subsidized housing units per 100 workers)

Enosburg: 10.1

Townshend: 9.7

Windsor: 9.4

Chester: 9.0

Fair Haven: 8.5

Vernon: 8.5 (note: data preceded Vermont Yankee closing)

Richford: 7.3

West Rutland: 6.9

Ludlow: 5.5

Hardwick: 5.2

Johnson: 5.2

Bradford Town: 5.2

Northfield: 4.9

Poultney: 4.8

Swanton: 4.8

Barton: 4.4

Londonderry: 4.3

Arlington: 4.0

Pittsford: 3.8

Castleton: 3.7

Jericho: 3.3

Putney: 3.2

Waitsfield: 3.1

Dorset: 3.0

Dover: 2.8

Barre Town: 2.8

Norwich: 2.5

Fairfax: 2.4

Bristol: 2.4

Richmond: 2.2

Hinesburg: 2.1

Warren: 1.7

Waterbury: 1.6

Derby: 1.5

Royalton: 1.4

Westminster: 1.1

Georgia: 0.9

Wilmington: 0.6

Rockingham: 0.6

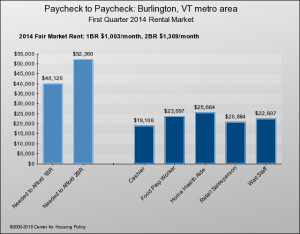

Now, when we bring income data into the mix, we find that there’s a rough, inverse correlation between median family income and the number of subsidized housing units. That’s not surprising. One might expect richer towns to have less housing for low-income people. The pattern doesn’t always hold, though.

Of the 14 municipalities that have no subsidized housing units, 10 have median family incomes above the state average, and four below.

And in the list above, four of the first five municipalities — the ones with the most subsidized units relative to their numbers of employees — are above average in median family income.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that there’s plenty of room to grow affordable housing in the more well-to-do municipalities. After all, shouldn’t lower-paid employees who work in those towns be able to live there? That’s in keeping with the goal of promoting fair housing choice for everyone in low-poverty, high-opportunity locations — places with ready access to good services, schools and transportation.