It wasn’t the failure of “forced busing” that led to current racial disparities in school achievement outcomes. The problem, rather, is that the nation’s schools have become more segregated over the last three decades, as integration dropped from the agenda of education policy-makers.

So wrote a Syracuse University education professor, George Theoharis, in an interesting piece in the Washington Post Sunday.

Two startling observations derive from his home town — which happens to be in our neck of the woods.

He notes the enormous disparities in programs, and outcomes, between a middle school with an 85 percent black and Latino student body and another middle school, 10 miles away, that’s 88 percent white. And he points out that in 1989, the city’s schools were about 60 percent white and 20 percent black/Latino, and that now, the district is 28 percent white, 55 percent black/Latino.

Theoharis goes on to discuss how a renewed emphasis on desegregation in educational policy could provide remedies: Redesigning school districts, for example, and putting them together “like pie pieces, so they cut across urban, suburban and even rural spaces”; or creating magnet schools; or providing incentives to school districts to desegregate.

(Note: Magnet schools were the Burlington School District’s remedy for socioeconomic achievement gaps.)

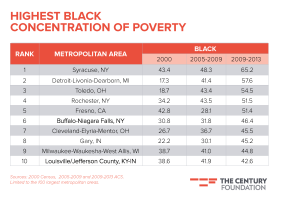

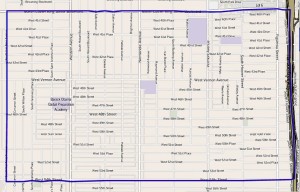

But Theoharis never delves into the heart of the matter: residential segregation. This has grown worse in many cities since 2000, with an increase in the number of high-poverty neighborhoods, as we noted in an earlier blog post citing “The Architecture of Segregation,” a paper that detailed the demographic trends. In Syracuse since 2000, according to that paper, “the number of high-poverty tracts more than doubled, rising from twelve to thirty… As a result, Syracuse now has the highest level of poverty concentration among blacks and Hispanics of the one hundred largest metropolitan areas,” as shown in this table:

The takeaway is that addressing residential segregation iskey to addressing school segregation. Another analysis of school segregation and racial performance disparities, by the Economic Policy Institute’s Richard Rothstein, put it like this:

“Education analysts frequently wonder why a black–white achievement gap remains, even when individual poverty and family characteristics are similar. Partly it’s because of greater (and multigenerational) segregation of black children into neighborhoods of high poverty, few employment opportunities, and frequent violence….

“It is inconceivable to think that education as a civil rights issue can be addressed without addressing residential segregation … Housing policy is school policy; equality of education relies upon eliminating the exclusionary zoning ordinances of white suburbs and subsidizing dispersed housing in those suburbs for low-income African Americans now trapped in central cities.”

That’s what affirmatively furthering fair housing is all about, right? But you already knew that.