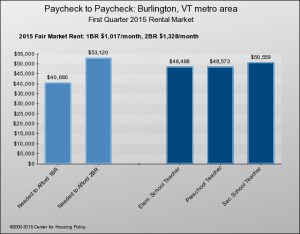

Here’s a seat-of-the-pants calculation that shows one dimension of Burlington’s (and Vermont’s) affordability problem for renters:

According to Vermont Housing Data, Burlington has 9,596 rental units. Of the households living in them, 61 percent are paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing — the standard threshold of unaffordability. By that standard, 5,853 rental units in Burlington are unaffordable to the people who live in them.

(The same source reports Vermont’s rental units at 69,581. More than half the households in those units – 52.5 percent – are paying more than 30 percent. That puts the state’s unaffordable rental units at 36,530.)

Those are just the figures for the standard housing burden. In Burlington, 35.7 percent of renters are severely burdened, paying more than 50 percent of their income on housing. That works out to 3,426 rental units that, for them, are severely unaffordable (and 18,369 such units statewide).

These are unsettling numbers, and of course there’s no easy remedy or policy panacea (although doubling public funding for affordable housing and raising the minimum wage to $15 would probably help).

Inclusionary zoning – which requires a specified percentage of units in new developments to be affordable – is among the policies that can be brought to bear. For a thorough, thoughtful treatment of the subject by Rick Jacobus, a Burlington alum, click here. He points out, among other things, that “inclusionary housing is one of the few proven strategies for locating affordable housing in asset-rich neighborhoods where residents are likely to benefit from access to quality schools, public services and better jobs.” In other words, it’s fully in keeping with the renewed national emphasis on affirmatively furthering fair housing.

He also writes that “inclusionary housing has yet to reach its full potential.” That’s an understatement in Vermont — one of 13 states that has statutes authorizing inclusionary policies that virtually no municipality except Burlington has taken advantage of – and in Burlington itself, where an inclusionary ordinance has been on the books for 25 years. Over that period, the policy has resulted in only about 260 affordable units (many of them condos).

That relatively low number reflects, in part, a lag in Burlington housing development in comparison to the rest of the county. What accounts for that, and is there any way the city’s inclusionary policy could be tweaked to make it more effective? Answers to these and other questions may be a year away. The Housing Action Plan calls for hiring a consultant to review the city’s inclusionary policy and make recommendations by next fall.