The Thriving Communities campaign will be doing a major outreach effort to bring many new people in to visit and participate in this new site in the near future. In the meantime we are inviting all visitors to comment on blogs and posts and to share the site with others.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Burlington’s housing-wage gap

Burlington needs more affordable housing, lots of it. Affordable rentals, especially. After all, renting households far outnumber owner households in this city, and by any measure, they’re financially stressed. On average, according to a city report last year, Burlington’s renters pay 44 percent of their income on housing. More than one-third of Burlington’s renters pay more than half their income on housing. That’s what’s known among housing specialists as a severe burden.

Because of inclusionary zoning, we can be fairly confident that new, affordable rental units will be made available wherever big new developments go in. The hope here, at the Fair Housing Project, is that such developments be spread around the city. Not all the new affordable units have to go in the Old North End!

The South End would seem to be prime candidate for more subsidized, multi-family housing, and as far as we’re concerned, the Hill should be another possibility. Granted, there’s a trade-off between the price of land and the number of units that can be developed on a given tract; but still, we support the idea of locating a decent share of new affordable housing in low-poverty areas.

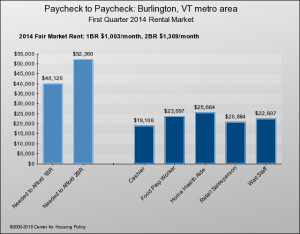

Here’s an interesting perspective on Burlington’s unaffordability from the point of view of low-wage workers. Consider five occupational categories that lead the state in numbers of workers: cashiers, personal care aids, retail salespeople, food prep workers and wait staff. Look at this graphic (courtesy of the National Housing Conference’s “Paycheck to Paycheck” that shows what annual income is needed to rent an apartment in Burlington without being burdened; and how their incomes compare:

Incidentally, personal care aide is one of the state’s fastest growing occupations. That’s a testament to the greying of Vermont, because personal care aides assist elderly or disabled adults. Is it too much to ask that personal care aides be able to find affordable housing in the same communities where they serve their clients?

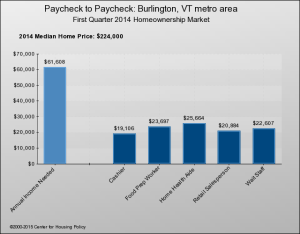

What about home ownership in Burlington for these workers? Similarly out of reach:

Jobs and affordable housing, Part 2

It’s not uncommon to hear Vermont employers complain that the high cost of housing is a deterrent to recruiting employees. Everyone knows Vermont needs more affordable housing. The question is, where should new affordable housing best be located?

The Fair Housing Project contends that it should be located near town centers, in mixed income areas that have good access to employment, transit and other services.

Some municipalities offer more affordable housing than others. In an effort to throw some light on where the needs are, we introduced the workforce housing index in our last post. This is the number of subsidized housing units for every 100 jobs in a town. Subsidized units are affordable, by definition, to people earning up to 80 percent the region’s median income, including workers in relatively low paying jobs. (Granted, affordable housing is also in short supply for middle-income workers – teachers or police officers, for example. A more comprehensive workforce housing index would take their needs into account, too.)

Without further ado, here’s how Vermont’s “major employment centers” rank in providing affordable housing. Again, the index is the number of subsidized housing units per 100 jobs:

Winooski: 24.5

Barre City: 9.9

Springfield: 7.5

Brattleboro: 6.9

Burlington: 6.8

Randolph: 6.3

Vergennes: 6.3

Rutland City: 6.1

St. Johnsbury: 5.9

St. Albans Town: 5.7

Bennington: 5.5

St. Albans City: 4.1

Manchester: 4.0

Montpelier: 3.9

Colchester: 3.7

Middlebury: 3.3

Newport: 3.2

South Burlington: 3.2

Lyndon: 2.9

Rutland Town: 2.7

Essex: 2.5

Stowe: 2.2

Morristown: 2.2

Hartford: 2.0

Williston: 1.7

Shelburne: 1.6

Waterbury: 1.6

Derby: 1.5

Milton: 1.4

Woodstock: 1.2

Rockingham: 0.6

A couple of observations: Municipalities with public housing authorities tend to rank high on the list, as might be expected. As for other towns that don’t have public housing authorities, well, some are clearly pulling their weight more than others.

In Chittenden County, Burlington and Winooski have the great majority of subsidized units, but they account for less than half the jobs. (The jobs total of Williston, South Burlington and Essex alone exceeds that of Burlington-Winooski.) Clearly, other Chittenden County towns have a ways to go in meeting the affordable housing needs of their workforces.

Jobs and affordable housing, Part 1

“Workforce housing” has become a popular term among housing advocates. Its definition varies, but for our purposes, it simply means affordable housing that’s fairly close to the workplaces of lower-and middle-income people.

Now, the ideal is that all the people who make a town’s economy run — the cashiers and the teachers, the home health-care aides and the police officers, the waitresses and the accountants, the secretaries and the tradespeople, from carpenters and plumbers to electricians — should all be able to live in town, if they want. That’s a form of population diversity — in skill sets, in housing options — that the Fair Housing Project wants to encourage: affordable housing for people of mixed incomes near their work sites.

Well then, one might well wonder how the job locations and the affordable housing units in Vermont match up … or don’t, town by town.

There’s no easy way to get at this, but here’s a proxy approach:

Look at municipalities that are employment centers and see how many units of subsidized housing they have.

Of course, “subsidized housing” typically refers to housing for people earning up to 80 percent of the median income, so it’s not the same as housing that accommodates a wide-ranging workforce of middle and above average incomes. But at least we can get an idea of which employment centers are more or less accommodating of lower-paid workers — the cashiers and personal care aides, for example, the two occupations with the most numerous openings in Vermont, according to the Department of Labor. We’ll assume that full-time cashiers and personal care aides qualify for subsidized housing. (Cashiers’ median hourly wage in Vermont last year was $9.73; personal care aides’, $10.99. By contrast, Vermont’s “housing wage” — the hourly rate needed to afford an average apartment without paying more than 30 percent of income– was $19.36.)

As for “employment centers” there were more than 80 Vermont municipalities that offered 500 jobs or more in 2014, according to Department of Labor statistics.

Of those, more than 30 had 2,000 jobs or more. Arbitrarily, we’ll call those the “major employment centers.”

To find out how many subsidized housing units each municipality has, we simply go to the Directory of Affordable Housing on the Housing Data website , pull up all the site-specific units for each town, and add them up.

With these two figures for each municipality — number of jobs and number of subsidized (affordable) housing units — we can derive a seat-of-the-pants workforce housing index: How many subsidized units for each 100 jobs. The higher the index, the more “workforce housing” that community provides.

Well, it turns out that all but one of Vermont’s major employment centers have a workforce housing index under 10 – that is, they each have fewer than 10 affordable housing units for every 100 workers.

The exception is Winooski, where the index is a whopping 24. (The city occupies a mere square mile, much of which is included in the aerial photo above.) Winooski had 2,799 jobs in 2014 and 687 subsidized housing units — the friendliest affordability ratio in Vermont by far.

Which major employment centers in Vermont had the fewest subsidized units? Stay tuned.

Here we go!

Welcome to the new website devoted to our “Thriving Communities” campaign. We’d like this space to become a Vermont forum for a continuing discussion of fair housing and affordable housing. These are two distinct but overlapping public policy concerns. They have something in common that we’ll get to in a moment.

Welcome to the new website devoted to our “Thriving Communities” campaign. We’d like this space to become a Vermont forum for a continuing discussion of fair housing and affordable housing. These are two distinct but overlapping public policy concerns. They have something in common that we’ll get to in a moment.

Fair housing means the absence of housing discrimination. The federal Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, sought to give Americans the right to live where they choose without begin discriminated against on the basis of race, color, national origin, or other protected characteristics. Vermont followed up with its own fair housing law about two decades later, expanding the list of protected categories.

Alas, housing discrimination is still with us. Thousands of individual complaints are filed across the country every year, and Vermont has its own share of violations. But beyond the individual cases are systemic, or organizational obstacles to fair housing choice, often in the form of planning, zoning or governmental policies that effectively restrict where certain people – particularly, those of lower income – can live. Nearly half a century after the Fair Housing Act was passed, much of our nation remains heavily segregated by race and by economic status.

Affordable housing, by the standard definition, is housing that doesn’t consume more than 30 percent of a household’s income. Families who pay more than that are termed “burdened”; and those who pay more than 50 percent, “severely burdened.” Unfortunately, these terms apply to a large share of Vermont’s renters. That’s because (a) market prices put housing out of reach, and (b) there aren’t anywhere near enough subsidized housing units to accommodate lower-income renters.

One goal of “Thriving Communities” – and of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, a key sponsor – is to reduce pockets of poverty and to proactively promote inclusive communities of high opportunity. We want to encourage municipalities to welcome more affordable housing – multi-family housing, in particular – that’s located in mixed-income neighborhoods, in close proximity to town centers, transit and other vital services.

OK, so what do these two issues – fair housing and affordable housing — have in common? They’re both off the political radar. Housing segregation and unaffordability are both major national problems, disadvantaging tens of millions, but they get very little attention from presidential candidates or Sunday talk shows.

Why the disconnect? We welcome your comments on this or on our posts to come. We’ll try to be newsy.