Category Archives: public opinion

Housing Equity & Preservation of Open Space

updated, 12/29/20

At the Fair Housing Project, we generally applaud community members who organize to get their needs better met. But this featured article in the Other Paper as part of the Vermont Community News Network begs a counter response. Continue reading Housing Equity & Preservation of Open Space

And another thing

This is the last grant-funded post, so we’ll try to keep it snappy, not sappy. What do we know about housing, anyway? Not a lot, but a good deal more than when we signed on to this gig 10 months ago.

For what they’re worth, we’ll leave you with a gratuitous thought and an anti-climactic ranking.

Housing can’t simply be left to the private market, any more than health care or education. It’s time for people to accept that resolving the housing-affordability crisis will require significant new governmental investment; and alleviating the socioeconomic and racial segregation that continue to stand in the way of fair housing choice, all across the country, will require concerted government intervention. Why shouldn’t the right to decent housing and fair housing choice be a public policy priority commensurate with the right to health care or the right to receive an education?

Rankings abound at New Year, so here’s one with an ancillary question: Rent or buy? 504 counties around the country are listed in order of rental affordability — that is, the percentage of local median income that’s required to pay median rent of three-bedroom apartment in that county. Also listed is the affordability percentage of a median priced home. Compare the percentages to see whether it’s more affordable to rent or buy.

No. 1 in rental affordability (or unaffordability) is Honolulu, at 73 percent. Buy. No. 505 is Huntsville, Ala., at 23 percent. Buy.

You can get to the Excel table by clicking here.

The only Vermont county in the table is Chittenden (listed as Burlington/South Burlington). Sorry, Bellows Falls, Bennington, et al, but that’s the way of these national surveys.

Burlington/South Burlington comes in at No. 152 in rental affordability, at 40 percent. Buying affordability: 46 percent. The recommendation: Rent.

That’s despite the fact that, according to the table, the cost of a 3 BR apartment in Burlington/South Burlington went up 12.2 percent in the last year.

Sounds a little high to us (so much for the 3.3 percent figure we’ve been hearing) but again, what do we know?

Could be worse.

Zoning’s link to unaffordability AND inequality

Rising income inequality has become a major public concern over the last few years. What some of us may not realize, though, is that zoning is one of the likely culprits.

Yes, zoning and other land-use restrictions can contribute to housing unaffordability, but also — by extension — to income inequality and diminishing productivity.

That’s the argument that Jason Furman, chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisors, brought to the Urban Institute in an address last month. His remarks had scholarly underpinnings, in the form of charts and footnotes.

Here’s a compressed version of what he said: Income inequality has increased over the last several decades, as have land-use restrictions in the more productive metropolitan areas. Meanwhile, labor mobility has declined — workers are less likely to switch jobs and move around the country for higher pay — and so have annual increases in productivity. The drop in mobility ( or “fluidity”) is not well understood, but one cause appears to be the high cost of housing in high-wage, productive cities (such as Boston or San Francisco) that many would-be employees can’t afford to move to.

“Zoning and other land-use restrictions, by restricting the supply of housing and so increasing its cost, may make it difficult for individuals to move to areas with better-paying jobs and higher-quality schools,” he said. (He acknowledged that some land-use restrictions can be beneficial, but that some can be harmfully excessive, in such forms as minimum lot sizes, off-street parking requirements, height limits, prohibitions on multifamily housing, and lengthy permitting processes.)

Hampered mobility diminishes economic growth, he said, citing the same recent study we referred to in a recent post.

Generally speaking, Furman said, zoning restrictions tend to favor well-to-do property owners, who defend these restrictions so as to safeguard their assets. Stringent zoning reduces housing supply, maintains high prices, reinforces wealthy enclaves, and effectively repels people of moderate or low income. The restrictiveness of land-use regulations correlates with the gap between construction costs and house prices — the bigger the gap, the more land costs figure into the those higher prices.

“The timing of tighter land use regulations may not have been a coincidence,” Furman said. “After a turbulent decade of the 1960s in the United States that saw racial tensions flare, with rioting in many urban areas around the country that damaged or destroyed both residential and commercial structures, thousands of high income, predominantly white families moved out of many cities, spurring the continued rise of racially and socioeconomically homogeneous communities. These communities were also strictly zoned, a choice which may very well have been a part of a conscious or unconscious attempt to maintain this homogeneity through the affordability channel.”

Nowadays, there’s an increased demand for multi-family housing, but this form of housing tends to be heavily regulated, he said, and one of the nation’s challenges is to reduce regulatory barriers to increasing the supply of this housing option. In fact, the Obama administration is promoting an initiative (the Multi-family Risk Sharing Mortgage) to shore up the “limited supply of credit” for multifamily developments.

What’s more, Obama’s FY16 budget includes $300 million for Local Housing Policy Grants — a competitive program, he said, designed to provide funds “to those localities and regional coalitions” that support “new zoning and land use regulations to create an expanded, more flexible and diverse housing supply.”

Hmm, any interest in Vermont?

New life for old idea?

When the housing-unaffordability problem comes up at a public meeting in Burlington, chances are someone will stand up and call for rent control.  Never mind that the city rejected the idea three decades ago and no one has made a serious effort to revive it locally. It’s an idea that never goes away, though, and is getting some fresh currency these days — where else, in California, the housing-unaffordability epicenter.

Never mind that the city rejected the idea three decades ago and no one has made a serious effort to revive it locally. It’s an idea that never goes away, though, and is getting some fresh currency these days — where else, in California, the housing-unaffordability epicenter.

Rent control’s heyday was in the ‘70s and ‘80s, apparently. Massachusetts did away with it in 1994 via a statewide vote, but it can still be found in many municipalities in New York, New Jersey and Maryland, as well as California, where tenants’ advocates are pushing to get more communities to sign on and have come up with an organizing toolkit. “Rent control moment gains momentum as housing prices soar,” read a recent news headline, but a closer look suggests that much of the impetus is in California. Most states, after all, have laws that prohibit rent control, although in Washington, there’s an effort to lift the ban for Seattle.

Any groundswell in favor of rent control would have to grow out of large numbers of renters, and renters are certainly on the increase nationally. A new Harvard report announces that “that 43 million families and individuals live in rental housing, an increase of nearly 9 million households since 2005 — the largest gain in any 10-year period on record.”

Renters are a distinct minority in Vermont, where the home-ownership rate is above average. In fact, renters outnumber homeowners in just two cities — Burlington and Winooski — so if rent control were plausible anywhere in Vermont, those would be the likely places. City voters would have to approve a charter change, which would require legislative approval. How unlikely is that?

Burlington voters overwhelmingly rejected rent control in a special election in 1981, during Bernie Sanders’ first mayoral term. (Actually, they rejected the creation of a “fair housing commission,” which everyone agreed was a proxy for rent control.) They were influenced by a publicity campaign against the measure mounted by commercial interests.  Sanders’ critics on the left complained he didn’t try very hard to see the idea through, and in fact he went on to promote affordable housing via a range of other policies.

Sanders’ critics on the left complained he didn’t try very hard to see the idea through, and in fact he went on to promote affordable housing via a range of other policies.

Barring a major ground shift, rent control will remain one of those recurrent policy ideas with no traction in these parts. Like single-payer health care.

Here a crisis, there a crisis

Never mind California or the Northeast. The housing-unaffordability problem can be found lots of other places, some of them rather unlikely. If you breeze through news coverage from around the country, you can find stories from all over that use the phrase “crisis” or “crunch” or “shortage” to describe the local or regional housing-unaffordability profile:

Just in the past few days, stories have bubbled up from Taos,  Jackson Hole, Aspen, Madison, Asheville, Hawaii, and Austin — all in crisis mode.

Jackson Hole, Aspen, Madison, Asheville, Hawaii, and Austin — all in crisis mode.

Austin is an interesting case: There’s not only an affordability shortage, most of the supposedly affordable units aren’t really affordable after all, according to a rather scathing audit that just came in. From the report summary: “The City does not have an effective strategy to meet its affordable housing needs. Neighborhood Housing and Community Development has not adopted clear goals, established timelines, or developed affordable housing numerical targets to evaluate its efforts in fulfilling the City’s adopted core values. Key information needed to evaluate program effectiveness is incomplete, inaccurate or unavailable.”  This, in the latter-day birthplace of public housing that the mayor pronounced the most economically segregated city in the country.

This, in the latter-day birthplace of public housing that the mayor pronounced the most economically segregated city in the country.

Among the places you might not expect to find a housing crisis: Minot, N.D., rural Iowa,  North Platte, Neb. (Say it ain’t so, North Platte!) And to think that this is not something the presidential candidates can even be bothered to talk about!

North Platte, Neb. (Say it ain’t so, North Platte!) And to think that this is not something the presidential candidates can even be bothered to talk about!

In fact, every county in the country can be said to be in crisis when it comes to housing extremely low-income households (that is, households with less than 30 percent of median income, 11.3 million nationwide). No county has enough units for such people, according to an analysis the Urban Institute did this summer. For an interactive map that will show you how many affordable units in each county for 100 poor households, click here. In Vermont, Orange, Windsor and Windham counties come out the best, with 49 affordable units for 100 households; Caledonia, Lamoille and Orleans have the fewest, at 29. The national average: 28.

Of course, the national challenge is not just to create plenty more affordable housing but to locate it judiciously. New housing options have to be provided for low-income people in low-poverty neighborhoods, otherwise known as “high-opportunity” areas. That’s what affirmatively furthering fair housing is about — breaking up historic settlement patterns of concentrated poverty and segregation and promoting integration.

Naturally, AFFH generates pushback. So, sprinkled among the wash of “housing crisis” stories are accounts of resistance to affordable housing projects in well-healed suburbs – such as Simsbury, Conn. (median household income$104,000) , and Wilmette, Ill. ($127,000).

Taller & brighter

Once upon a time, believe it or not, planners of public housing in the United States believed high rises were a good thing. In the early ‘40s, we learn from J.A. Stoloff’s history of public housing, the thought high-rises “could provide a healthy, unique living environment that would contrast favorably with surrounding slum areas.”

Well, as we all know, high-rises for families didn’t work too well in the big metro areas. Two notorious examples in Chicago were Cabrini Green …

and Robert Taylor Homes…

drab, unsightly, unlivable in many ways, they unfortunately tainted the popular conception of public housing. No public-housing high-rises were built after the early ‘70s, and by the ‘90s many of these buildings were being torn down.

As it turned out, though, some public-housing high-rises did work pretty well – for elderly residents. One such example, built in 1971, is the tallest building in Vermont – 11-story Decker Towers in Burlington, operated by the Burlington Housing Authority for elderly and disabled residents:

Granted, construction of ANY public housing is passe in this country, sadly, but before you stop thinking about high-rises, look at some examples in Singapore, where public-housing high-rises are home to a majority of the population. These shots are by Peter Steinhauer, a photographer:

These photos make two things really clear: (1) High rises don’t have to be drab and dreary…

… and (2) no one should have any trouble finding the street address of these places.

The bright colors bring to mind some of the buildings in Burlington’s Old North End, many of them owned or developed by Stu McGowan …

Now that we’ve drawn your attention back to Vermont, let’s consider building height on a Vermont scale as we also consider how to add to the state’s affordable housing stock. High rises are out of the question, of course, especially in our small towns. But what about adding a third story to buildings in town centers, here and there, for family apartments? Is that such an outrageous idea? This three-story building in the photo below doesn’t look a bit out of place.

Housing opinions get short shrift in D.C.

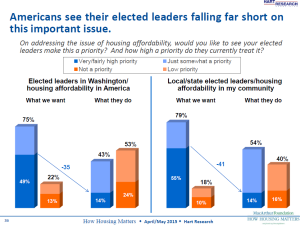

You may have missed it, but the MacArthur Foundation, by way of Hart Research Associates, did a national poll of 1,401 adults last spring on housing issues – the third such survey since the Great Recession. Guess what: A majority thought the housing crisis isn’t over yet!

No surprise there, given that 60 percent said they regard housing affordability as a “serious problem,” and 55 percent said they’d made at least one sacrifice (e.g. taking second job, eating more junk food, etc.) to cover their housing costs.

We’ll spare you the responses to the questions on class mobility and Millennial stresses, and simply highlight a couple of disconnects:

- Respondents appeared divided about what role, if any, the federal government has in addressing the housing-affordability problem. Fifty-three percent said it wasn’t the federal government’s responsibility, compared to 39 percent who thought the federal government should be involved.

And yet, a big majority – 75 percent – said they want elected leaders in Washington to make housing affordability a priority. (See? We’re not alone in saying stuff like this, or this.) And 79 percent said they wanted state and local elected leaders to do so.

- But those elected leaders – national, state and local – are not making affordable housing enough of a priority, at least in respondents’ eyes, as suggested by this chart:

Dare we suggest a reason why public officials are not responding? Because they have a sense of impunity, inasmuch as making affordable housing a high priority would, in all likelihood, require spending appreciable amounts of tax dollars. How would the poll’s respondents feel about that?