Category Archives: middle class

Nagging question

How does an affordable housing development affect surrounding property values?

There’s no simple answer to this question, in part because of the many variables that come into play– the siting, for example, and the nature of the neighborhood (blighted? well-to-do?), the scale of the development, the design, and so on.

Not surprisingly, though, the question has spawned a large literature. A rather dated survey of the research, from the Furman Center at NYU, found that “the vast majority of studies have found that affordable housing does not depress neighboring property values, and may even raise them in some cases.” A “Field Guide to Effects of Low-Income Housing on Property Values,” put out by the National Association of Realtors and citing numerous references, updated last year, agrees: “Most studies indicate that affordable housing has no long term negative impact on surrounding home values.”

Indeed, that’s the standard pitch that affordable-housing advocates make in the face of NIMBY opposition: The notion that affordable housing drives down property values is a “myth.”

Then, along comes a study with an inconvenient conclusion, seemingly muddying the water. That would be “Who Wants Affordable Housing in their Backyard? An Equilibrium Analysis of Low Income Property Development,” by Stanford economists Rebecca Diamond and Tim McQuade. Their finding is that, within a 0.1-mile radius, Low Income Housing Tax Credit-financed developments raise property values over the long run in low-income neighborhoods but lower them in higher-income neighborhoods. They conclude: “Given the goals of many affordable housing polices is to decrease income and racial segregation in housing markets, these goals might be better achieved by investing in affordable housing in low income and high minority areas, which will then spark in-migration of high income and a more racially diverse set of residents.”

This conclusion runs contrary to the spirit of affirmatively furthering fair housing, which advocates a balanced approach for affordable housing investment: revitalizing blighted areas, on one hand, and desegregating higher-income areas, on the other. This dual approach also has the imprimatur of the U.S. Supreme Court, which effectively endorsed it in its ruling this summer upholding the disparate impact doctrine. (For our previous post on this, click here.) The court’s ruling favored a Texas plaintiff who argued that affordable housing projects should NOT be disproportionately sited in low-income minority neighborhoods.

While we await critiques of the Stanford study from the affordable-housing commentariat, we take note of various examples where affordable housing has not depressed property values in higher-income communities: Places such as Mount Laurel, N.J., epicenter of New Jersey’s fair/affordable housing movement, where a Princeton study found that values in surrounding neighborhoods were unaffected (for the New York Times account, click here). Or Weston or Wellesley, two of Massachusetts’ wealthiest communities, where a Tufts study found that mixed-income developments had no effect on surrounding property values, as reported via Shelterforce.

One factor that might well have a bearing, and that would not show up in the Census-tract-type data used by the Stanford researchers, is design. Affordable housing doesn’t have to look cheap or barracks-y. In fact, if the design is done well, affordable units can be hard to distinguish from market-rate units.

Planning consultant Julie Campoli demonstrates this in her “Thriving Communities” webinar/seminar presentation. She shows each of the following two slides of four photos each and asks viewers to guess which is affordable and which market-rate. We’re giving the answer away by showing the labeled versions here, but her point should be obvious.

Good news, mostly

- Little backyard houses — aka “accessory dwelling units” — are springing up all over Vancouver.

This is a partial remedy to the affordable rental shortage that afflicts municipalities all over North America, including Vermont. It also affords an optional living arrangement for older people who want to age in place. In Vancouver, these appendages are called “laneway houses,” and some of them are pretty handsome. There’s plenty of room for additions like this in Burlington, even if we don’t have alleys — and in plenty of other Vermont communities, too.

This is a partial remedy to the affordable rental shortage that afflicts municipalities all over North America, including Vermont. It also affords an optional living arrangement for older people who want to age in place. In Vancouver, these appendages are called “laneway houses,” and some of them are pretty handsome. There’s plenty of room for additions like this in Burlington, even if we don’t have alleys — and in plenty of other Vermont communities, too. - A “mobility program” in heavily segregated Baltimore moves families from high-poverty public housing complexes in the city to higher-rent, higher-opportunity suburbs. This is an initiative very much in the spirit of affirmatively furthering fair housing, but it serves a small fraction of the subsidy-eligible families in need and it operates largely under the radar, to minimize opposition. One obstacle: a shortage of affordable housing in suburban communities.

- Plattsburgh has a new 64-unit affordable housing complex, called Homestead on Ampersand.

It’s just a couple of miles from the neighborhood where complaints about a proposal for a smaller affordable housing complex prevailed.

It’s just a couple of miles from the neighborhood where complaints about a proposal for a smaller affordable housing complex prevailed. - Columbus, Ohio, plans to transform a vacant downtown building into “workforce housing” – which in this case means housing for people who make $40,000 to $60,000 a year. The made-over building would feature micro units – apartments of 300 square feet or so and targeted, presumably, to single Millennials. We’ve touched on the micro movement before, which seems to be taking hold mostly in bigger metro areas (here’s a roundup with a national map; for a more substantial study of the phenomenon, click here). But it has also spread to Kalamazoo and, as we’ve noted, Syracuse, so there’s no reason it couldn’t work in an over-priced city like Burlington, where officialdom is forever wringing its hands about how young professionals have trouble finding affordable accommodations.

Renters arise!

Since 2005, the number of renters in this country has gone up 9 million, to 41 million, the biggest surge of any decade on record. That brings the share of renting households to 37 percent, the highest in half a century. Meanwhile, their rents are up and their incomes are down: From 2001 to 2014, rents rose 7 percent (above inflation) and incomes dropped by 9 percent.

The biggest increase in renter households, surprisingly, came from the Baby Boomer cohort – people in their 50s and 60s. In fact households 40 and older make up the majority of renters.

These are among the findings in “America’s Rental Housing,” a 44-page study out this week from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Not only are there many more renters, but many more of those renters can’t comfortably afford to live where they do. In 2014, 49 percent of renters were “burdened” (meaning they paid more than 30 percent of their incomes for rent and utilities) and 26 percent were “severely burdened” (more than 50 percent). According to Vermont Housing Data, Vermont’s current rates are a tad higher: 52.5 percent and 26.4 percent.

Yes, the housing burden falls most heavily on low-income people, but it’s growing among the middle-income stratum as well:

“(T)he sharpest growth in cost-burdened shares has been among middle-income households. The share of burdened households with incomes in the $30,000–44,999 range increased from 37 percent in 2001 to 48 percent in 2014, while that of households with incomes of $45,000–74,999 nearly doubled from 12 percent to 21 percent. Regardless of income level, though, the shares of cost-burdened households reached new peaks in 2014 among all but the highest-income renters.”

Meanwhile, only about one-fourth of eligible lower-income households receive housing assistance (Section 8 vouchers are not an entitlement!); funding for HUD’s three biggest rental assistance programs is about the same (corrected for inflation) as it was seven years ago, when the economy crashed; and the HOME program, a major source of federal funding for housing programs, has been cut way back. Private developers continue to add to the multi-family housing supply, but most of the recent additions “serve the higher end of the market,” according to the report. As it happens, high-income households (annual $100,000 or more) represent a small but fast-growing share of the rental market.

The report asserts:

“The challenge now facing the country is to ensure that a sufficient and appropriate supply of rental housing is available for a diversity of households and in a diversity of locations. While the private market has proven capable of expanding the higher-end rental stock, developers have only limited opportunities to meet the needs of lowest income households without subsidies that close the large gap between construction costs and what these renters can afford to pay. In many high-cost markets, moderate-income households face affordability challenges as well.”

“Diversity of locations” is an invocation of AFFH (affirmatively furthering fair housing) and the goal of ensuring that a good share of affordable housing is in “high-opportunity” neighborhoods,” as in what follows:

“Policymakers urgently need to consider the extent and form of housing assistance that can stem the rapid growth in cost burdened households. Beyond affordability, they also need to promote development of a wider range of housing options so that more renter households can find homes that suit their needs and in communities offering good schools and access to jobs. It will take concerted efforts by all levels of government to capitalize on the capabilities of the private and not-for-profit sectors to reach this goal.”

Dare we suggest that concerted efforts have yet to be mounted, or even contemplated, by government at many levels?

Extracurricular accommodations

There’s a particular form of workforce housing that’s getting a lot of attention lately: affordable housing for teachers. Much of that attention is being paid in California, of course, where many school districts are having trouble recruiting and retaining teachers who can’t afford the prohibitive housing costs (in Silicon Valley, for example, or San Francisco, where the mayor has announced plans to build 500 affordable units for teachers). Similar plans are afoot in Oakland, San Mateo, L.A.

But housing complexes for teachers have arisen on the East Coast, too, mostly in bigger cities — Newark (pictured), Baltimore and Philadelphia, with a development in Springfield, Mass., in the pipeline. These are projects aimed at Teach for America recruits for these cities — recent college graduates who spend two or three years in public or charter schools before they move on to other pursuits.

Baltimore and Philadelphia, with a development in Springfield, Mass., in the pipeline. These are projects aimed at Teach for America recruits for these cities — recent college graduates who spend two or three years in public or charter schools before they move on to other pursuits.

Not all the teacher-housing initiatives are urban, though. Several counties in North Carolina have provided, or pledged to provide, affordable housing for teachers, as has McDowell County, W. Va., in a project carried out with the American Federation of Teachers. In West Virginia, the hope is that the housing will help attract teachers to a place where they otherwise wouldn’t be inclined to settle.

Other states use housing as a teacher-recruitment tool in different ways. Oklahoma offers low-interest loans, for example. Texas offers mortgage assistance for teachers, and Mississippi subsidizes down-payments and closing costs. These happen to be states with pronounced teacher shortages.

Vermont has a teacher shortage, too — perhaps not as dire as those states’, but a shortage nevertheless. According to the Agency of Education’s “Designated Shortage Areas” for 2015-16, teachers of English, Spanish and special education were needed in all counties, and math teachers were needed in half the counties. Could it be that Vermont’s housing costs are a barrier to teacher recruitment? And if so, would it make sense for school districts — which are being encouraged to merge anyway — to collaborate in finding ways to ease the housing burden?

Another line of argument is that school districts, instead of futzing with housing benefits, should simply pay teachers well enough so that they can afford to live in those districts.

In any case, teacher villages, or housing complexes, come in different forms, and it’s not always clear how they gibe with affirmatively furthering fair housing standards. The one in Newark, for example, has been criticized as an oasis for transient young white professionals in a gentrifying neighborhood. (For a nice overview of these programs in The American Prospect, click here.) Still, Vermont communities would do well to think about how they can make affordable housing available to middle-income people – such as teachers – who are hard pressed to pay market rates.

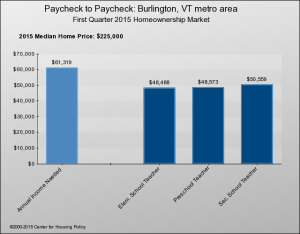

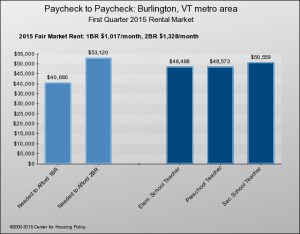

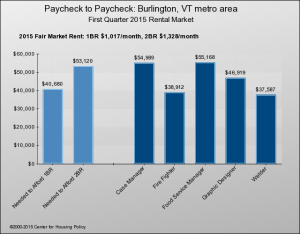

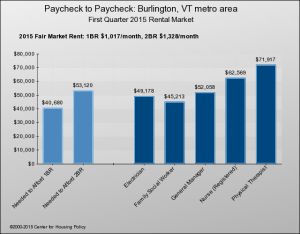

Consider educators in the Burlington metro area. The National Housing Conference’s interactive “Paycheck to Paycheck” matches housing costs (the annual salary needed to afford a house of median price, $225,000) and the salary needed to afford a one-bedroom or two-bedroom apartment.

When you run the model for three educators – preschool, primary and secondary school teachers — you find that:

They can’t comfortably afford the median mortgage…

… or the two-bedroom apartment…

Tampering with the sacrosanct

The presidential candidates have a lot to say about tax reform, but with one exception, they’re not about to get rid the big sacred cow — the mortgage-interest deduction, found on Schedule A of Form 1040:![]()

Economists have been complaining about the mortgage-interest deduction for years. It’s a regressive benefit, increasing with income. It enhances inequality, effectively inflates property values and misallocates resources, or so the argument goes. In 2012, the mortgage interest deduction cost the federal government $70 billion, according to the Urban Institute, compared $36 billion for low-income housing subsidies.

But nobody expects that deduction to go away any time soon. It’s a firmly entrenched loophole (aka “third rail”) not only for the wealthy elite, but for the simple majority. The home ownership rate in this country exceeds 60 percent (in Vermont, it’s over 70 percent), and of course the lion’s share of those people are mortgage-holder beneficiaries.

The ranks of renters are increasing, though, and the more they do, the more seriously they might be taken as a political constituency. Politicians take renters seriously in Germany, where renters are in the majority and the regulatory climate is much more in their favor. Germany doesn’t offer a mortgage-interest deduction, either.

Might the growing numbers of American renters be mobilized to support the elimination of the mortgage-interest deduction — which ostensibly doesn’t benefit them anyway — in favor of increased housing subsidies for low- and moderate-income tenants? That seems like a stretch, unless another Occupy-style movement sweeps the country.

Well, if eliminating the mortgage-interest deduction discourages home ownership, so be it. There’s even evidence that home ownership isn’t necessarily such a wonderful thing, because it damages labor markets:

“We find that rises in the home- ownership rate in a U.S. state are a precursor to eventual sharp rises in unemployment in that state,” write economists David Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald, in a 2013 paper. Why? Partly because higher rates of homeownership curtail labor mobility and lead to longer commutes.

So, who’s the exception among the presidential candidates? Ben Carson.  He’s the only one who has said he’d do away with the mortgage-interest deduction. (Even Bernie Sanders doesn’t go that far – he’d cap it at $300,000.) For a full-throated defense of this Carson stance from someone who doesn’t agree with much of anything else he says, click here.

He’s the only one who has said he’d do away with the mortgage-interest deduction. (Even Bernie Sanders doesn’t go that far – he’d cap it at $300,000.) For a full-throated defense of this Carson stance from someone who doesn’t agree with much of anything else he says, click here.

Learning from Massachusetts

The Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2015 is out, and it’s an eye-opener. Prepared for the Boston Foundation by the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University, it’s a detailed analysis of Massachusetts’ housing-unaffordability crisis –a crisis that results, in part, from not enough housing being produced. What accounts for the insufficiency?

“We have failed to meet housing production targets because there is no way to do so given the high cost of producing housing for working and middle-income households.”

That’s from the executive summary, which goes on to make the same point in another way:

“(T)he cost of developing new housing for working and middle-income households has become prohibitive in Massachusetts. Radical remedies will be needed to overcome the barriers to housing production …”

And what are the barriers? High development costs, of course ($274 per square foot for urban projects, of which $159 is construction and $41 is land acquisition). And zoning regulations that limit density and where multi-family projects can be built.

Now, you might be thinking, what does any of this have to do with us, up here in our little, rural, unprepossessing state? Metro Boston is another world — far pricier and denser than any place around here.

Well, we’d argue that the problems that Massachusetts is facing are problems we share — albeit on a smaller scale. And remember, Massachusetts has an affordable housing zoning law (Chapter 40B) that’s arguably stronger than what’s on Vermont’s books.

Yes, it would be nice if we could get a comparable report card for housing in Vermont, but failing that, perhaps we can learn something from what the one for Massachusetts.

The report notes that “Although there is a lot of vacant land, most vacant sites are not zoned for multi-family residential development.”

As for zoning:

“Highly restrictive zoning, present in virtually every one of the state’s 351 municipalities, creates an artificially high barrier to development. It pushes developers to propose smaller projects (i.e., fewer units) and smaller units (i.e., fewer bedrooms per unit) in order to reduce the perceived impact on the neighborhoods and — in the case of larger units attractive to families with school-age children — the perceived impact on the town or city’s education budget. The complexity of getting zoning changes approved dramatically extends the development period and increases carrying and soft costs. The cumulative effect drives up both the cost of development (seen in the high level of site costs, financing, and soft costs) and rents.

“Thus, significant resistance to any change in the local community ambience has also meant that local support has heavily favored low-density, smaller projects, both of which are far more expensive to produce. Higher density housing maximizes the efficiency of land use, and larger projects create economies of scale in development and construction. Massachusetts residents opposed to zoning for multi-family housing at 20 units per acre are astounded to learn that the city of Paris — a pretty nice place to live with undeniable “character” — has a density of approximately 120 units per acre!

“When developers are given permission only to build projects of very low density, they will do so. As a result, the housing that is built will be expensive and affordable only for the very well-to-do or, if public subsidies are involved, to people with very low incomes. Working and moderate-income families will not be able to afford these units. This state of affairs, of course, causes the average cost of producing multifamily housing in the Commonwealth to increase.”

Here we note that merely increasing the housing supply (as some are advocating) isn’t going to solve the affordability problem if the added supply happens to be … luxury-scale and thus … unaffordable to all but the wealthy.

More brainstorming: self-building

The housing-unaffordability problem is too big, pervasive and complex to yield to single, simple remedies. Yes, government at all levels has to play a substantially bigger role than it does now. But without substantial new federal funding and subsidies — which can’t be found on mainstream politicians’ lists of spending priorities — we might as well brainstorm about piecemeal, alternative solutions.

Having touched on co-living and cohousing in the last post, we bring you a continental variant of this idea: collective building.

This intriguing headline in the Guardian, “The do-it-yourself answer to Britain’s housing crisis,” offers an entrée: community members, with help from a land trust, building their own affordable homes. Britain even has an organization, the National Custom and Self-Build Association, to promote such efforts.

Self-building seems to be an even bigger trend on the continent. In Germany, baugruppen, or building groups, are active all over, and reportedly account for 10 percent of new homes built in Berlin.  These are groups of people who come together, often with something in common (they might be musicians, say, or share a political philosophy), and take responsibility for acquiring land, hiring architects and contractors, and creating their own housing. For a summary of how it works, click here, or another brief description, here.

These are groups of people who come together, often with something in common (they might be musicians, say, or share a political philosophy), and take responsibility for acquiring land, hiring architects and contractors, and creating their own housing. For a summary of how it works, click here, or another brief description, here.

The baugruppe is a well-established form of organization in Germany and apparently gets a good deal of institutional support, including financing from a state bank. Whether something like this could work in this country is an open question.

Mike Eliason, a designer who was author of a seven-part series on baugruppen, seems to think it could, at least in a place like Seattle. For the first article, on the website of a Seattle advocacy organization called The Urbanist, click here. As Eliason describes it, baugruppen projects cost less than traditional models because they do without developers and marketing, as well as real estate agents.

It all sounds reminiscent of cohousing, except that it’s commonly done in an urban setting — as the photos in this post reflect. It also sounds like a fairly middle-class phenomenon, considering how much of a personal investment it requires of its participants. Who has the time and energy necessary to do all the meeting and planning and hiring and so on? Probably not someone who holds down two minimum-wage jobs. Not that we don’t need affordable housing, sometimes called workforce housing, for middle-class professional types, too.

Sleeper issue snoozes on

We’ve read through the transcripts of the two GOP-presidential-candidate debates held on CNBC last night, in order that — to steal one of Gail Collins’ recurrent lines — you don’t have to do it.

We’ve read through the transcripts of the two GOP-presidential-candidate debates held on CNBC last night, in order that — to steal one of Gail Collins’ recurrent lines — you don’t have to do it.

The two debates, of course, featured the “undercard,” with four candidates, and the “main card,” with 10.

In nearly four hours of discussion, the word “housing” was uttered once. That was when Rand Paul lambasted the Federal Reserve Board for, among other alleged malfeasances, having “caused the housing boom and the crisis…”

The candidates had nothing to say — nor were they asked by their CNBC interlocutors — about the housing unaffordability that afflicts millions of Americans, or about persistent residential segregation by race and income. And they had virtually nothing to say about the bubble-burst that ushered in the Great Recession. Maybe that’s partly because the bubble was fed by the kind of deregulation that small-government proponents are fond of promoting.

True, six of these candidates had been given brief opportunities to hold forth at a daylong “housing summit” in New Hampshire that we noted last week (here’s yet another account of that event, by the way), but it seems unlikely they were each talked out after that experience. Perhaps they, their fellow contenders, and the CNBC panel all agree with Chris Christie’s comment at the summit that housing is an unsexy issue that “kind of depresses people.”

On the other hand, the candidates talked a lot last night about other things they presumably think are depressing, such as ”big government” and taxes. One might have expected that housing could get some attention in a debate that was supposed to focus on economic matters.

Perhaps the candidates believe that their various plans for shrinking government and “growing” the economy will jump-start the private market to spur housing development, raise incomes of working families, and take care of the affordable housing problem. If so, it would be nice if they’d explain in some detail how that will work.

It would be even nicer if reporters would start making them talk about it.

Stuck in the middle

Middle-class financial struggles have occupied the public discourse for some time, but wouldn’t you know, we’re starting to hear more about housing unaffordability as a stresser for this beleaguered population segment.

The annual “State of the Nation’s Housing” report from Harvard took note this summer:

While long a condition of low-income households, cost burdens are spreading rapidly among moderate-income households. The cost-burdened share of renters with incomes in the $30,000–45,000 range rose 7 percentage points between 2003 and 2013, to 45 percent. The increase for renters earning $45,000–75,000 was almost as large at 6 percentage points, affecting one in five of these households. On average, in the ten highest-cost metros—including Boston, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco—three-quarters of renters earning $30,000–45,000 and just under half of those earning $45,000–75,000 had disproportionately high housing costs.”

Granted, much of the news about middle-class housing unaffordability is coming out of the big cities – places where “middle income” is construed to reach far above Vermont standards. For example, Cambridge, Mass., is taking steps to reserve a share of “affordable” housing in a new Kendall Square building for families with incomes in the low six figures! San Francisco is also considering measures that would expand affordable housing eligibility and help out renters in the $100,000 to $140,000 bracket. And Portland, Ore., where the “housing emergency” is apparently wide-ranging, is looking at a form of inclusionary zoning that make apartments available to people making 100 120 percent of the median income (Up to $96,875 for a family of four).

Perhaps it’s a testament to the severity of the housing crisis around the country, and/or to the fragility of the middle-income stratum, that the terms “middle class” and “subsidy” are suddenly being spoken in the same breath.

Here’s the thing: To qualify for most subsidized housing, applicants can’t earn more than 80 percent of the local median income. Where does that leave people who draw an average salary, or perhaps a little more? Perhaps in a place where they can’t readily afford housing but can’t get any help, either. How many such people there are in Vermont is unclear; plenty, no doubt.

(Note: Middle-income earners are not beneficiaries of Burlington’s inclusionary zoning ordinance, which aims to provide affordable rentals for people earning up to 65 percent of the median; and for sale, up to 75 percent.)

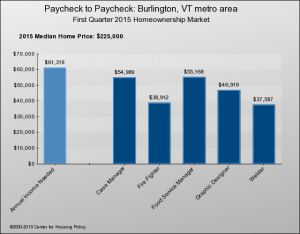

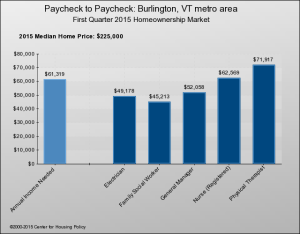

For an illustrative display of how housing costs compare to standard incomes, the National Housing Conference’s interactive “Paycheck to Paycheck” shows bar graphs for each of the nation’s metro areas – and just one in Vermont, Burlington/South Burlington. One graph compares salaries to the pay needed to afford a median-priced home; another does the same thing for 1- and 2-BR apartments at HUD’s “fair market rent.”

Below are the charts for 10 occupations that might be considered to be middle class. As you can see, eight of the 10 would be hard pressed to afford purchase of an average home in Burlington:

They do a little better in the rental market, but still, six of 10 can’t comfortably afford a two-bedroom apartment in Burlington: