Continue reading “Without Stable Shelter, Everything Else Falls Apart”

Category Archives: income inequality

The Fair Housing Act at 50 | Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies

Fair housing can and should be a centerpiece of efforts to expand economic opportunity, asserted Dr. Raphael Bostic, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, who gave the 18th Annual John T. Dunlop Lectureat the Harvard Graduate School of Design on Tuesday, April 10 (watch video). His talk, on the past, present, and future of the Fair Housing Act, was given one day before the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the measure.

Bostic, who also served as Assistant Secretary for Policy Development and Research at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) from 2009 until 2012, explained that decades of research show the strong positive impacts that neighborhoods can have on children’s education and future earnings. Given this, he noted, it is in everyone’s interest to support efforts to expand opportunities for all families. “Fair housing is a key to economic mobility,” he explained. “It is an economic development issue as well as a community and personal development issue.” …

Read more-

Source: Housing Perspectives (from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies)

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies advances understanding of housing issues and informs policy.

Important Federal Funding Facts About Housing in America

OUR HOMES, OUR VOICES

THE CAMPAIGN FOR HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FUNDING

Information sheet produced by the National Low Income Housing Coalition

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.thrivingcommunitiesvt.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/OurHomes-OurVoices7-2017.pdf”]

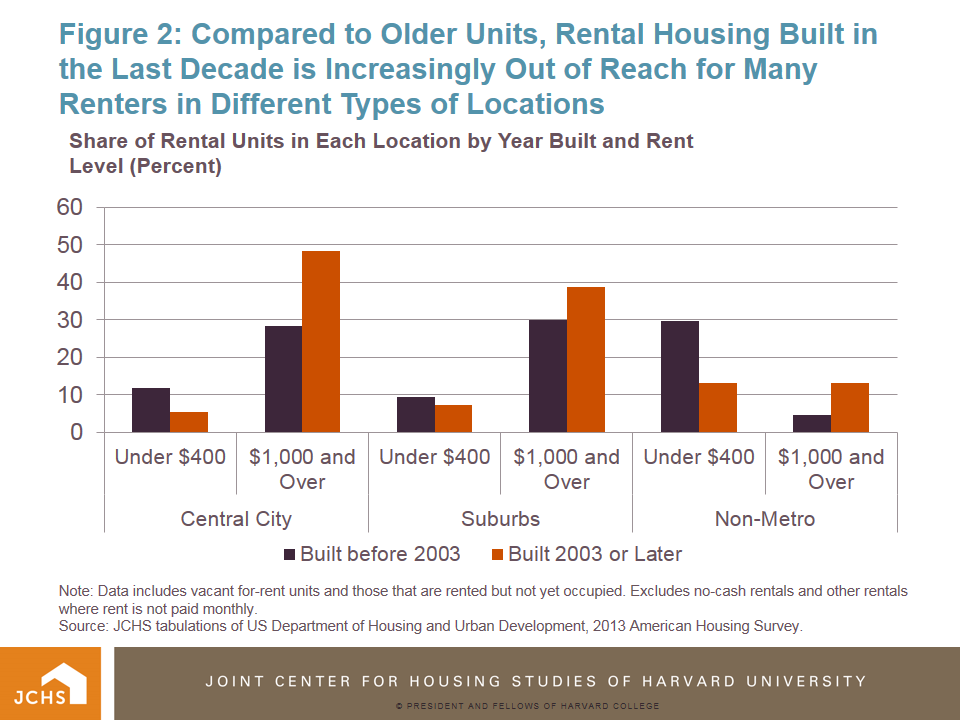

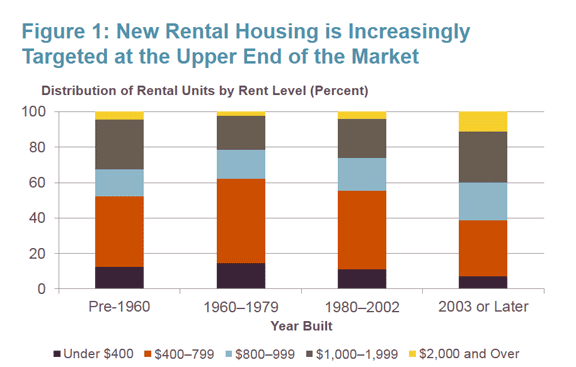

New Rental Development: nationally the cost is slanted upward

A higher percentage of people are renting their homes in the U.S. than has been the case for many decades. The market is responding with more rental housing development – but there is a big glitch – too much of that new rental housing now being developed is on the high end of the affordability spectrum.

This article: “Surge in New Rental Construction Fails to Meet Need for Low-Cost Housing,” by Irene Lew, at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, offers a thorough and informative analysis of the current situation – which is not a good one for moderate to low income people in our communities.

“…the housing affordability crisis has shown little signs of abating in recent years, as renter incomes continue to lag behind rising housing costs. Though there has been a ramp-up in rental housing construction, much of this new housing is intended for renters at the upper end of the income spectrum…”

“…the housing affordability crisis has shown little signs of abating in recent years, as renter incomes continue to lag behind rising housing costs. Though there has been a ramp-up in rental housing construction, much of this new housing is intended for renters at the upper end of the income spectrum…”

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2013 American Housing Survey.

Not so easy

A key goal of affirmatively furthering fair housing (AFFH), as it’s envisioned playing out around the country, is to break up concentrations of poverty and to promote socioeconomic and racial integration. That means ensuring opportunities for lower-income people and racial minorities to live in wealthier, “high opportunity” neighborhoods with access to jobs, goods schools and public services.

Two ways to facilitate those opportunities:

- Promote regional mobility among people with Section 8 vouchers, enabling them to leave high-poverty areas and move into more well-to-do communities. This can require increasing their housing allowance so that they can afford higher suburban rents.

- Build affordable, multifamily rental housing in those same, heretofor exclusive neighborhoods.

Both of these approaches deserve consideration around here, as Vermonters contemplate how to make their communities more socioeconomically inclusive. Meanwhile, it’s interesting to see how they’ve played out in an entirely different environment: metropolitan Baltimore.

First, some background: Baltimore has a long history of racial segregation (click here for a trenchant account), and in the mid-1990s, the Department of Housing and Urban Development was sued by city residents (Thompson vs. HUD) for its failure to eliminate segregation in public housing. In 2005, a federal judge found that HUD had violated the Fair Housing Act by maintaining existing patterns of impoverishment and segregation in the city and by failing to achieve “significant desegregation” in the Baltimore region.

Seven years later, a court-approved settlement resolved the case in a way that anticipated the AFFH rule that HUD issued this past summer.

The settlement called on HUD to continue the Baltimore Mobility Program, begun in 2003 in an earlier settlement phase. The program has provided housing vouchers to more than 2,600 families to move out of poor, segregated neighborhoods and into areas with populations that are less than 10 percent impoverished and less than 30 percent black. The program provides counseling before and after the move and has received high marks from evaluators who cite improved educational and employment outcomes for beneficiaries. A similar regional program is underway in Chicago.

The settlement also called for affordable-housing development in these “high-opportunity” suburban communities – 300 units a year through 2020. To make this happen, HUD was to provide new financial incentives for developers.

Here is where the story takes a dispiriting turn. Three years later, not a single developer has applied for the incentives. No affordable housing projects are even in the pipeline. That’s according to an eye-opening story the other day in the Baltimore Sun.

So, what happened? Why haven’t developers shown any interest? HUD had no explanation, according to the story, which suggested that perhaps the program hadn’t been well-enough publicized: a prominent builder of affordable housing admitted he didn’t even know about the incentives. Could it be that they weren’t generous enough?

Whatever the reason, the Baltimore experience reflects how difficult it can be to introduce affordable housing to privileged enclaves. No one should underestimate the AFFH challenge.

Nagging question

How does an affordable housing development affect surrounding property values?

There’s no simple answer to this question, in part because of the many variables that come into play– the siting, for example, and the nature of the neighborhood (blighted? well-to-do?), the scale of the development, the design, and so on.

Not surprisingly, though, the question has spawned a large literature. A rather dated survey of the research, from the Furman Center at NYU, found that “the vast majority of studies have found that affordable housing does not depress neighboring property values, and may even raise them in some cases.” A “Field Guide to Effects of Low-Income Housing on Property Values,” put out by the National Association of Realtors and citing numerous references, updated last year, agrees: “Most studies indicate that affordable housing has no long term negative impact on surrounding home values.”

Indeed, that’s the standard pitch that affordable-housing advocates make in the face of NIMBY opposition: The notion that affordable housing drives down property values is a “myth.”

Then, along comes a study with an inconvenient conclusion, seemingly muddying the water. That would be “Who Wants Affordable Housing in their Backyard? An Equilibrium Analysis of Low Income Property Development,” by Stanford economists Rebecca Diamond and Tim McQuade. Their finding is that, within a 0.1-mile radius, Low Income Housing Tax Credit-financed developments raise property values over the long run in low-income neighborhoods but lower them in higher-income neighborhoods. They conclude: “Given the goals of many affordable housing polices is to decrease income and racial segregation in housing markets, these goals might be better achieved by investing in affordable housing in low income and high minority areas, which will then spark in-migration of high income and a more racially diverse set of residents.”

This conclusion runs contrary to the spirit of affirmatively furthering fair housing, which advocates a balanced approach for affordable housing investment: revitalizing blighted areas, on one hand, and desegregating higher-income areas, on the other. This dual approach also has the imprimatur of the U.S. Supreme Court, which effectively endorsed it in its ruling this summer upholding the disparate impact doctrine. (For our previous post on this, click here.) The court’s ruling favored a Texas plaintiff who argued that affordable housing projects should NOT be disproportionately sited in low-income minority neighborhoods.

While we await critiques of the Stanford study from the affordable-housing commentariat, we take note of various examples where affordable housing has not depressed property values in higher-income communities: Places such as Mount Laurel, N.J., epicenter of New Jersey’s fair/affordable housing movement, where a Princeton study found that values in surrounding neighborhoods were unaffected (for the New York Times account, click here). Or Weston or Wellesley, two of Massachusetts’ wealthiest communities, where a Tufts study found that mixed-income developments had no effect on surrounding property values, as reported via Shelterforce.

One factor that might well have a bearing, and that would not show up in the Census-tract-type data used by the Stanford researchers, is design. Affordable housing doesn’t have to look cheap or barracks-y. In fact, if the design is done well, affordable units can be hard to distinguish from market-rate units.

Planning consultant Julie Campoli demonstrates this in her “Thriving Communities” webinar/seminar presentation. She shows each of the following two slides of four photos each and asks viewers to guess which is affordable and which market-rate. We’re giving the answer away by showing the labeled versions here, but her point should be obvious.

Renters’ agenda

The Center for American Progress has put out a report that nicely ties together, in summary fashion, the current status of fair housing and unaffordable housing. These are the mainstay, overlapping concerns of the “Thriving Communities” campaign. If you’re looking for a fairly brief (33 pages) treatment of where things stand, complete with an array of federal policy recommendations, “An Opportunity Agenda for Renters” is worth a look.

The report touches on many of the topics we’ve mentioned in this blog — the persistence of racial and socioeconomic segregation, the barriers to mobility from impoverished to high-opportunity areas, the growing financial burdens on the growing class of renters in the face of woefully insufficient public subsidies.

One of the policy recommendations, naturally, is that the primary federal vehicle for creating or preserving affordable housing be expanded. That’s the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, which accounts for about 110,000 residential units a year, according to the report. But even if that program were increased by 50 percent, as called for by the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Housing Commission, the total number of units created or preserved would still be way too few, considering “the current shortage of 4.5 million units that are affordable to extremely low-income households.”

As things stand, the federal tax code benefits homeowners in several ways, and disproportionately the wealthier ones. The mortgage-interest tax deduction alone costs the government about $70 billion a year. By contrast, increasing funding of the Section 8 program to cover 3 million eligible low-income renters who are shut out of the program now would cost just $22 billion.

Here’s another proposal in renters’ favor: creating a federal renters’ tax credit. A modest tax credit benefiting the lowest income renters could cost a mere $5 billion.

Vermont’s renter rebate is better than nothing, but it still doesn’t go very far. In 2012, according to a 2014 report to the Legislature, 13,541 claimants (about one-fifth of the state’s renting households) received a total of $8.7 million in rebates, for an average of $641. That $641 was not enough to unburden the typical claimant.

“On average,” the report stated, “Vermont’s renter rebate program reduces gross rent as a percent of household income from 36.7 percent to 33.6 percent.”

In other words, the average renter was living in an unaffordable place even after the rebate.

Zoning’s link to unaffordability AND inequality

Rising income inequality has become a major public concern over the last few years. What some of us may not realize, though, is that zoning is one of the likely culprits.

Yes, zoning and other land-use restrictions can contribute to housing unaffordability, but also — by extension — to income inequality and diminishing productivity.

That’s the argument that Jason Furman, chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisors, brought to the Urban Institute in an address last month. His remarks had scholarly underpinnings, in the form of charts and footnotes.

Here’s a compressed version of what he said: Income inequality has increased over the last several decades, as have land-use restrictions in the more productive metropolitan areas. Meanwhile, labor mobility has declined — workers are less likely to switch jobs and move around the country for higher pay — and so have annual increases in productivity. The drop in mobility ( or “fluidity”) is not well understood, but one cause appears to be the high cost of housing in high-wage, productive cities (such as Boston or San Francisco) that many would-be employees can’t afford to move to.

“Zoning and other land-use restrictions, by restricting the supply of housing and so increasing its cost, may make it difficult for individuals to move to areas with better-paying jobs and higher-quality schools,” he said. (He acknowledged that some land-use restrictions can be beneficial, but that some can be harmfully excessive, in such forms as minimum lot sizes, off-street parking requirements, height limits, prohibitions on multifamily housing, and lengthy permitting processes.)

Hampered mobility diminishes economic growth, he said, citing the same recent study we referred to in a recent post.

Generally speaking, Furman said, zoning restrictions tend to favor well-to-do property owners, who defend these restrictions so as to safeguard their assets. Stringent zoning reduces housing supply, maintains high prices, reinforces wealthy enclaves, and effectively repels people of moderate or low income. The restrictiveness of land-use regulations correlates with the gap between construction costs and house prices — the bigger the gap, the more land costs figure into the those higher prices.

“The timing of tighter land use regulations may not have been a coincidence,” Furman said. “After a turbulent decade of the 1960s in the United States that saw racial tensions flare, with rioting in many urban areas around the country that damaged or destroyed both residential and commercial structures, thousands of high income, predominantly white families moved out of many cities, spurring the continued rise of racially and socioeconomically homogeneous communities. These communities were also strictly zoned, a choice which may very well have been a part of a conscious or unconscious attempt to maintain this homogeneity through the affordability channel.”

Nowadays, there’s an increased demand for multi-family housing, but this form of housing tends to be heavily regulated, he said, and one of the nation’s challenges is to reduce regulatory barriers to increasing the supply of this housing option. In fact, the Obama administration is promoting an initiative (the Multi-family Risk Sharing Mortgage) to shore up the “limited supply of credit” for multifamily developments.

What’s more, Obama’s FY16 budget includes $300 million for Local Housing Policy Grants — a competitive program, he said, designed to provide funds “to those localities and regional coalitions” that support “new zoning and land use regulations to create an expanded, more flexible and diverse housing supply.”

Hmm, any interest in Vermont?