Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts senator, gave a speech Sunday in Boston that the website “Salon” called “the realest talk on race by any American politician.” She delivered her remarks at the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate as part of a “Getting to the Point” lecture series.

She had something to say about violence, about voting, and about economic justice – and economic justice as it relates to housing. Some excerpts:

“For most middle class families in America, buying a home is the number one way to build wealth. It’s a retirement plan-pay off the house and live on Social Security. An investment option-mortgage the house to start a business. It’s a way to help the kids get through college, a safety net if someone gets really sick, and, if all goes well and Grandma and Grandpa can hang on to the house until they die, it’s a way to give the next generation a boost-extra money to move the family up the ladder.

“For much of the 20th Century, that’s how it worked for generation after generation of white Americans – but not black Americans. Entire legal structures were created to prevent African Americans from building economic security through home ownership. Legally-enforced segregation. Restrictive deeds. Redlining. Land contracts. Coming out of the Great Depression, America built a middle class, but systematic discrimination kept most African-American families from being part of it.

“State-sanctioned discrimination wasn’t limited to homeownership. The government enforced discrimination in public accommodations, discrimination in schools, discrimination in credit-it was a long and spiteful list.”

Here we interject that she’s just scratching the surface of the federal government’s tawdry history of promoting residential segregation by race. For an eye-opening summation, check out what Richard Rothstein, of the Economic Policy Institute, had to say at the recent HUD conference in Washington. See the video we posted previously.

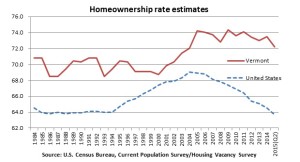

We note also the racial disparity in home ownership. In 2010, in Vermont, according to the 2012 “Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice,” the home-ownership for whites (71.4 percent) was nearly twice that for blacks (32.5 percent).

Warren went on to talk inequality over the last few decades, including the disparate effects of predatory lending that preceded the housing crash:

“Research shows that the legal changes in the civil rights era created new employment and housing opportunities. In the 1960s and the 1970s, African-American men and women began to close the wage gap with white workers, giving millions of black families hope that they might build real wealth.

“But then, Republicans’ trickle-down economic theory arrived. Just as this country was taking the first steps toward economic justice, the Republicans pushed a theory that meant helping the richest people and the most powerful corporations get richer and more powerful. I’ll just do one statistic on this: From 1980 to 2012, GDP continued to rise, but how much of the income growth went to the 90% of America – everyone outside the top 10% – black, white, Latino? None. Zero. Nothing. 100% of all the new income produced in this country over the past 30 years has gone to the top ten percent.

“Today, 90% of Americans see no real wage growth. For African-Americans, who were so far behind earlier in the 20th Century, this means that since the 1980s they have been hit particularly hard. In January of this year, African-American unemployment was 10.3% – more than twice the rate of white unemployment. And, after beginning to make progress during the civil rights era to close the wealth gap between black and white families, in the 1980s the wealth gap exploded, so that from 1984 to 2009, the wealth gap between black and white families tripled.

“The 2008 housing collapse destroyed trillions in family wealth across the country, but the crash hit African-Americans like a punch in the gut. Because middle class black families’ wealth was disproportionately tied up in homeownership and not other forms of savings, these families were hit harder by the housing collapse. But they also got hit harder because of discriminatory lending practices-yes, discriminatory lending practices in the 21st Century. Recently several big banks and other mortgage lenders paid hundreds of millions in fines, admitting that they illegally steered black and Latino borrowers into more expensive mortgages than white borrowers who had similar credit. Tom Perez, who at the time was the Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, called it a “racial surtax.” And it’s still happening – earlier this month, the National Fair Housing alliance filed a discrimination complaint against real estate agents in Mississippi after an investigation showed those agents consistently steering white buyers away from interracial neighborhoods and black buyers away from affluent ones. Another investigation showed similar results across our nation’s cities. Housing discrimination alive and well in 2015.”