Category Archives: housing vouchers

Important Federal Funding Facts About Housing in America

OUR HOMES, OUR VOICES

THE CAMPAIGN FOR HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FUNDING

Information sheet produced by the National Low Income Housing Coalition

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.thrivingcommunitiesvt.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/OurHomes-OurVoices7-2017.pdf”]

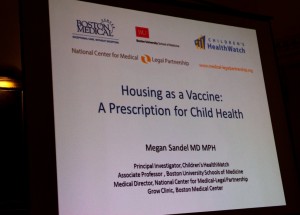

Housing as a Vaccine

The 2016 Homelessness Awareness Day and Vigil was held at the Vermont State House in Montpelier on January 7th. Two House committees Housing, General and Military Affairs and Human Services had a joint hearing on homelessness, taking testimony on housing and homelessness issues. A number of other hearings regarding homelessness happened in the building during the course of the day.

Opening the hearing was nationally recognized pediatrician Dr. Megan Sandel (principal investigator on Children’s Health Watch, Associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine, and Medical director, at the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership at Boston Medical Center), who has done path-breaking work on the effects of housing insecurity and homelessness on children. She gave a brilliant presentation on “Housing as a Vaccine: A Prescription for Child Health.”

At that hearing, Representatives and attending members of the public also heard from Vermont homeless service providers Linda Ryan (Director of Samaritan House) and Sara Kobylenski (Executive Director of Upper Valley Haven) on the latest trends and some recommended solutions to end or decrease homelessness in Vermont.

At Noon, community members, legislative leaders, administration officials, and advocates took the State House steps for a vigil to remember our friends and neighbors who died without homes, and to bring awareness of the struggles of those still searching for safe and secure housing. U.S. Senator Patrick Leahy and other legislative representatives and advocates joined and spoke at the vigil.

How can Housing be a Vaccine?

Dr. Megan presented data to support her thesis that housing can be protective for health. The quality, stability and affordability are important determinants to heath of all people. That means improving housing can provide multiple benefits. According to Dr. Megan, timing and duration of housing insecurity matter greatly to a child’s health. By increasing availability, affordability, and quality of housing, the health effect of housing insecurity can be decreased. Dr. Megan also provided specific evidence regarding housing quality and children’s health. For example, developmental issues, worsening asthma and other conditions have been tied to specific housing conditions such as pests, mold, tobacco smoke, lead exposure and so forth, and tied to long term effect with poor health outcomes.

According to Children’s Health Watch, “unstable housing, hunger and health are linked” because evidence shows that being behind on rent is strongly associated with negative health outcomes such as high risk of child food insecurity, children and mothers who are more likely in fair or poor health, children who are more likely at risk for development delay, mothers who are more likely experiencing depressive symptoms. Research conducted by the National Housing Conference from Children’s Healthwatch illustrates that there is no safe level of homelessness. The timing (pre-natal, post-natal) and duration of homelessness (more or less than six month) compound the risk of harmful childhood health outcomes. The younger and longer a child experiences homelessness, the greater the cumulative toll of negative health outcomes, which can have lifelong effects on the child, the family, and the community.

Several community representatives spoke in support of increasing housing affordability by targeting more public funding to support housing affordability and housing stability and adding to state housing directed funds with a $2 per night fee on hotel, motel and inn stays.

Not so easy

A key goal of affirmatively furthering fair housing (AFFH), as it’s envisioned playing out around the country, is to break up concentrations of poverty and to promote socioeconomic and racial integration. That means ensuring opportunities for lower-income people and racial minorities to live in wealthier, “high opportunity” neighborhoods with access to jobs, goods schools and public services.

Two ways to facilitate those opportunities:

- Promote regional mobility among people with Section 8 vouchers, enabling them to leave high-poverty areas and move into more well-to-do communities. This can require increasing their housing allowance so that they can afford higher suburban rents.

- Build affordable, multifamily rental housing in those same, heretofor exclusive neighborhoods.

Both of these approaches deserve consideration around here, as Vermonters contemplate how to make their communities more socioeconomically inclusive. Meanwhile, it’s interesting to see how they’ve played out in an entirely different environment: metropolitan Baltimore.

First, some background: Baltimore has a long history of racial segregation (click here for a trenchant account), and in the mid-1990s, the Department of Housing and Urban Development was sued by city residents (Thompson vs. HUD) for its failure to eliminate segregation in public housing. In 2005, a federal judge found that HUD had violated the Fair Housing Act by maintaining existing patterns of impoverishment and segregation in the city and by failing to achieve “significant desegregation” in the Baltimore region.

Seven years later, a court-approved settlement resolved the case in a way that anticipated the AFFH rule that HUD issued this past summer.

The settlement called on HUD to continue the Baltimore Mobility Program, begun in 2003 in an earlier settlement phase. The program has provided housing vouchers to more than 2,600 families to move out of poor, segregated neighborhoods and into areas with populations that are less than 10 percent impoverished and less than 30 percent black. The program provides counseling before and after the move and has received high marks from evaluators who cite improved educational and employment outcomes for beneficiaries. A similar regional program is underway in Chicago.

The settlement also called for affordable-housing development in these “high-opportunity” suburban communities – 300 units a year through 2020. To make this happen, HUD was to provide new financial incentives for developers.

Here is where the story takes a dispiriting turn. Three years later, not a single developer has applied for the incentives. No affordable housing projects are even in the pipeline. That’s according to an eye-opening story the other day in the Baltimore Sun.

So, what happened? Why haven’t developers shown any interest? HUD had no explanation, according to the story, which suggested that perhaps the program hadn’t been well-enough publicized: a prominent builder of affordable housing admitted he didn’t even know about the incentives. Could it be that they weren’t generous enough?

Whatever the reason, the Baltimore experience reflects how difficult it can be to introduce affordable housing to privileged enclaves. No one should underestimate the AFFH challenge.

Renters’ agenda

The Center for American Progress has put out a report that nicely ties together, in summary fashion, the current status of fair housing and unaffordable housing. These are the mainstay, overlapping concerns of the “Thriving Communities” campaign. If you’re looking for a fairly brief (33 pages) treatment of where things stand, complete with an array of federal policy recommendations, “An Opportunity Agenda for Renters” is worth a look.

The report touches on many of the topics we’ve mentioned in this blog — the persistence of racial and socioeconomic segregation, the barriers to mobility from impoverished to high-opportunity areas, the growing financial burdens on the growing class of renters in the face of woefully insufficient public subsidies.

One of the policy recommendations, naturally, is that the primary federal vehicle for creating or preserving affordable housing be expanded. That’s the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, which accounts for about 110,000 residential units a year, according to the report. But even if that program were increased by 50 percent, as called for by the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Housing Commission, the total number of units created or preserved would still be way too few, considering “the current shortage of 4.5 million units that are affordable to extremely low-income households.”

As things stand, the federal tax code benefits homeowners in several ways, and disproportionately the wealthier ones. The mortgage-interest tax deduction alone costs the government about $70 billion a year. By contrast, increasing funding of the Section 8 program to cover 3 million eligible low-income renters who are shut out of the program now would cost just $22 billion.

Here’s another proposal in renters’ favor: creating a federal renters’ tax credit. A modest tax credit benefiting the lowest income renters could cost a mere $5 billion.

Vermont’s renter rebate is better than nothing, but it still doesn’t go very far. In 2012, according to a 2014 report to the Legislature, 13,541 claimants (about one-fifth of the state’s renting households) received a total of $8.7 million in rebates, for an average of $641. That $641 was not enough to unburden the typical claimant.

“On average,” the report stated, “Vermont’s renter rebate program reduces gross rent as a percent of household income from 36.7 percent to 33.6 percent.”

In other words, the average renter was living in an unaffordable place even after the rebate.

Good news, mostly

- Little backyard houses — aka “accessory dwelling units” — are springing up all over Vancouver.

This is a partial remedy to the affordable rental shortage that afflicts municipalities all over North America, including Vermont. It also affords an optional living arrangement for older people who want to age in place. In Vancouver, these appendages are called “laneway houses,” and some of them are pretty handsome. There’s plenty of room for additions like this in Burlington, even if we don’t have alleys — and in plenty of other Vermont communities, too.

This is a partial remedy to the affordable rental shortage that afflicts municipalities all over North America, including Vermont. It also affords an optional living arrangement for older people who want to age in place. In Vancouver, these appendages are called “laneway houses,” and some of them are pretty handsome. There’s plenty of room for additions like this in Burlington, even if we don’t have alleys — and in plenty of other Vermont communities, too. - A “mobility program” in heavily segregated Baltimore moves families from high-poverty public housing complexes in the city to higher-rent, higher-opportunity suburbs. This is an initiative very much in the spirit of affirmatively furthering fair housing, but it serves a small fraction of the subsidy-eligible families in need and it operates largely under the radar, to minimize opposition. One obstacle: a shortage of affordable housing in suburban communities.

- Plattsburgh has a new 64-unit affordable housing complex, called Homestead on Ampersand.

It’s just a couple of miles from the neighborhood where complaints about a proposal for a smaller affordable housing complex prevailed.

It’s just a couple of miles from the neighborhood where complaints about a proposal for a smaller affordable housing complex prevailed. - Columbus, Ohio, plans to transform a vacant downtown building into “workforce housing” – which in this case means housing for people who make $40,000 to $60,000 a year. The made-over building would feature micro units – apartments of 300 square feet or so and targeted, presumably, to single Millennials. We’ve touched on the micro movement before, which seems to be taking hold mostly in bigger metro areas (here’s a roundup with a national map; for a more substantial study of the phenomenon, click here). But it has also spread to Kalamazoo and, as we’ve noted, Syracuse, so there’s no reason it couldn’t work in an over-priced city like Burlington, where officialdom is forever wringing its hands about how young professionals have trouble finding affordable accommodations.

Surprise! Some rents going down

Burlington’s chronic housing-affordability problem is bad enough — more than a third of the city’s 9,500 renting households are paying more than half their income for rent and utilities, which puts them in the “severely burdened” category — but guess what? It’s getting arguably worse.

HUD just came out with its 2016 fair market rents for the Burlington/South Burlington metro area, and they’re lower than they were for 2015. This despite the fact that actual rents in this area have been going up every year. (The 2016 numbers are up and down across the state, as Vermont Housing Finance Agency’s news blog helpfully details.)

If you really want to know why Burlington’s numbers went down, you can go to the HUD page to see the methodology. The unfortunate upshot, though, is that anyone with a Section 8 housing voucher is going to have less to choose from in 2016 than they do this year. That’s because apartments that cost more than the “fair market rent” are off-limits for subsidy. (If it makes you feel any better, remember that majority of Burlington’s “burdened” households don’t have vouchers anyway. Nationally HUD rental assistance extends to only about one-fourth of the people who are income-eligible.)

OK, let’s consider a two-bedroom apartment. The 2016 “fair market rent” is $1,172 (as compared to 2015’s $1,302). What are the offerings on Craigslist?

Here are the first 10 listed rents for two-bedroom apartments in Burlington and environs (South Burlington, Colchester) that we found at noon Monday. (Craigslist is constantly updated, so if you do the search the results will vary):

$2,500, $1,600, $2,500, $2,100, $1,425, $2,400, $2,025, $2,000, $2,000, $1,650.

How “fair” is that market? Now, perhaps Craiglist rents tend to be above average (are there studies that document this?), but there’s not much consolation in that, especially if you have a housing-choice voucher.

Renters arise!

Since 2005, the number of renters in this country has gone up 9 million, to 41 million, the biggest surge of any decade on record. That brings the share of renting households to 37 percent, the highest in half a century. Meanwhile, their rents are up and their incomes are down: From 2001 to 2014, rents rose 7 percent (above inflation) and incomes dropped by 9 percent.

The biggest increase in renter households, surprisingly, came from the Baby Boomer cohort – people in their 50s and 60s. In fact households 40 and older make up the majority of renters.

These are among the findings in “America’s Rental Housing,” a 44-page study out this week from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Not only are there many more renters, but many more of those renters can’t comfortably afford to live where they do. In 2014, 49 percent of renters were “burdened” (meaning they paid more than 30 percent of their incomes for rent and utilities) and 26 percent were “severely burdened” (more than 50 percent). According to Vermont Housing Data, Vermont’s current rates are a tad higher: 52.5 percent and 26.4 percent.

Yes, the housing burden falls most heavily on low-income people, but it’s growing among the middle-income stratum as well:

“(T)he sharpest growth in cost-burdened shares has been among middle-income households. The share of burdened households with incomes in the $30,000–44,999 range increased from 37 percent in 2001 to 48 percent in 2014, while that of households with incomes of $45,000–74,999 nearly doubled from 12 percent to 21 percent. Regardless of income level, though, the shares of cost-burdened households reached new peaks in 2014 among all but the highest-income renters.”

Meanwhile, only about one-fourth of eligible lower-income households receive housing assistance (Section 8 vouchers are not an entitlement!); funding for HUD’s three biggest rental assistance programs is about the same (corrected for inflation) as it was seven years ago, when the economy crashed; and the HOME program, a major source of federal funding for housing programs, has been cut way back. Private developers continue to add to the multi-family housing supply, but most of the recent additions “serve the higher end of the market,” according to the report. As it happens, high-income households (annual $100,000 or more) represent a small but fast-growing share of the rental market.

The report asserts:

“The challenge now facing the country is to ensure that a sufficient and appropriate supply of rental housing is available for a diversity of households and in a diversity of locations. While the private market has proven capable of expanding the higher-end rental stock, developers have only limited opportunities to meet the needs of lowest income households without subsidies that close the large gap between construction costs and what these renters can afford to pay. In many high-cost markets, moderate-income households face affordability challenges as well.”

“Diversity of locations” is an invocation of AFFH (affirmatively furthering fair housing) and the goal of ensuring that a good share of affordable housing is in “high-opportunity” neighborhoods,” as in what follows:

“Policymakers urgently need to consider the extent and form of housing assistance that can stem the rapid growth in cost burdened households. Beyond affordability, they also need to promote development of a wider range of housing options so that more renter households can find homes that suit their needs and in communities offering good schools and access to jobs. It will take concerted efforts by all levels of government to capitalize on the capabilities of the private and not-for-profit sectors to reach this goal.”

Dare we suggest that concerted efforts have yet to be mounted, or even contemplated, by government at many levels?

NIMBY notes from all over

Fresh news of NIMBY opposition to affordable housing comes out of … well, our own backyard.

From North Country Public Radio, we learn that residents in Plattsburgh managed to persuade the planning board to reject a proposed four-building residential complex, alleging familiar sorts of adverse effects that low-income people would have on traffic, safety, property values.  Affordable housing is a permitted use in that district, but…

Affordable housing is a permitted use in that district, but…

“It is transient housing,” one resident complained. “ They put people in there who are just out of jail, prison whatever until they can get back on their feet … I don’t want it in my area.”

“This concept of us serving transients is so far from reality,” countered the director of the housing organization that would be referring tenants. “The majority of the people that we serve are disabled. They are the veterans in your community. There are elderly people in your community that we serve…”

She might have also cited reports, like this one, that affordable housing can have an uplifting impact on economic development and property values.

Oh well. The developer is appealing the rejection in court. “The thrust of it was, they did not want ‘these people’ moving into their neighborhood,” the developer’s lawyer said.

Plattsburgh is in good company. Upper Saddle River, a toney community in New Jersey, is being sued for rejecting a multi-family housing complex, and thus, by proxy, new residents who happen to be black or Latino. Another interesting case of NIMBY opposition to multi-family housing recently arose in Arizona, where the “backyard” in question belonged to a mortuary! Apparently the mortuary and the developer resolved their differences, though.

NIMBYism gets some of the credit, or blame, for California’s housing-affordability crisis, and it certainly comes in many forms, as this entertaining catalogue attests. Among our favorites are “mega-mansion NIMBYs.”

Daunting affordability gaps

Here’s a seat-of-the-pants calculation that shows one dimension of Burlington’s (and Vermont’s) affordability problem for renters:

According to Vermont Housing Data, Burlington has 9,596 rental units. Of the households living in them, 61 percent are paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing — the standard threshold of unaffordability. By that standard, 5,853 rental units in Burlington are unaffordable to the people who live in them.

(The same source reports Vermont’s rental units at 69,581. More than half the households in those units – 52.5 percent – are paying more than 30 percent. That puts the state’s unaffordable rental units at 36,530.)

Those are just the figures for the standard housing burden. In Burlington, 35.7 percent of renters are severely burdened, paying more than 50 percent of their income on housing. That works out to 3,426 rental units that, for them, are severely unaffordable (and 18,369 such units statewide).

These are unsettling numbers, and of course there’s no easy remedy or policy panacea (although doubling public funding for affordable housing and raising the minimum wage to $15 would probably help).

Inclusionary zoning – which requires a specified percentage of units in new developments to be affordable – is among the policies that can be brought to bear. For a thorough, thoughtful treatment of the subject by Rick Jacobus, a Burlington alum, click here. He points out, among other things, that “inclusionary housing is one of the few proven strategies for locating affordable housing in asset-rich neighborhoods where residents are likely to benefit from access to quality schools, public services and better jobs.” In other words, it’s fully in keeping with the renewed national emphasis on affirmatively furthering fair housing.

He also writes that “inclusionary housing has yet to reach its full potential.” That’s an understatement in Vermont — one of 13 states that has statutes authorizing inclusionary policies that virtually no municipality except Burlington has taken advantage of – and in Burlington itself, where an inclusionary ordinance has been on the books for 25 years. Over that period, the policy has resulted in only about 260 affordable units (many of them condos).

That relatively low number reflects, in part, a lag in Burlington housing development in comparison to the rest of the county. What accounts for that, and is there any way the city’s inclusionary policy could be tweaked to make it more effective? Answers to these and other questions may be a year away. The Housing Action Plan calls for hiring a consultant to review the city’s inclusionary policy and make recommendations by next fall.