The Center for American Progress has put out a report that nicely ties together, in summary fashion, the current status of fair housing and unaffordable housing. These are the mainstay, overlapping concerns of the “Thriving Communities” campaign. If you’re looking for a fairly brief (33 pages) treatment of where things stand, complete with an array of federal policy recommendations, “An Opportunity Agenda for Renters” is worth a look.

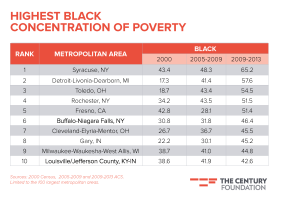

The report touches on many of the topics we’ve mentioned in this blog — the persistence of racial and socioeconomic segregation, the barriers to mobility from impoverished to high-opportunity areas, the growing financial burdens on the growing class of renters in the face of woefully insufficient public subsidies.

One of the policy recommendations, naturally, is that the primary federal vehicle for creating or preserving affordable housing be expanded. That’s the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, which accounts for about 110,000 residential units a year, according to the report. But even if that program were increased by 50 percent, as called for by the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Housing Commission, the total number of units created or preserved would still be way too few, considering “the current shortage of 4.5 million units that are affordable to extremely low-income households.”

As things stand, the federal tax code benefits homeowners in several ways, and disproportionately the wealthier ones. The mortgage-interest tax deduction alone costs the government about $70 billion a year. By contrast, increasing funding of the Section 8 program to cover 3 million eligible low-income renters who are shut out of the program now would cost just $22 billion.

Here’s another proposal in renters’ favor: creating a federal renters’ tax credit. A modest tax credit benefiting the lowest income renters could cost a mere $5 billion.

Vermont’s renter rebate is better than nothing, but it still doesn’t go very far. In 2012, according to a 2014 report to the Legislature, 13,541 claimants (about one-fifth of the state’s renting households) received a total of $8.7 million in rebates, for an average of $641. That $641 was not enough to unburden the typical claimant.

“On average,” the report stated, “Vermont’s renter rebate program reduces gross rent as a percent of household income from 36.7 percent to 33.6 percent.”

In other words, the average renter was living in an unaffordable place even after the rebate.