Never mind California or the Northeast. The housing-unaffordability problem can be found lots of other places, some of them rather unlikely. If you breeze through news coverage from around the country, you can find stories from all over that use the phrase “crisis” or “crunch” or “shortage” to describe the local or regional housing-unaffordability profile:

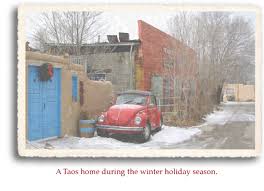

Just in the past few days, stories have bubbled up from Taos,  Jackson Hole, Aspen, Madison, Asheville, Hawaii, and Austin — all in crisis mode.

Jackson Hole, Aspen, Madison, Asheville, Hawaii, and Austin — all in crisis mode.

Austin is an interesting case: There’s not only an affordability shortage, most of the supposedly affordable units aren’t really affordable after all, according to a rather scathing audit that just came in. From the report summary: “The City does not have an effective strategy to meet its affordable housing needs. Neighborhood Housing and Community Development has not adopted clear goals, established timelines, or developed affordable housing numerical targets to evaluate its efforts in fulfilling the City’s adopted core values. Key information needed to evaluate program effectiveness is incomplete, inaccurate or unavailable.”  This, in the latter-day birthplace of public housing that the mayor pronounced the most economically segregated city in the country.

This, in the latter-day birthplace of public housing that the mayor pronounced the most economically segregated city in the country.

Among the places you might not expect to find a housing crisis: Minot, N.D., rural Iowa,  North Platte, Neb. (Say it ain’t so, North Platte!) And to think that this is not something the presidential candidates can even be bothered to talk about!

North Platte, Neb. (Say it ain’t so, North Platte!) And to think that this is not something the presidential candidates can even be bothered to talk about!

In fact, every county in the country can be said to be in crisis when it comes to housing extremely low-income households (that is, households with less than 30 percent of median income, 11.3 million nationwide). No county has enough units for such people, according to an analysis the Urban Institute did this summer. For an interactive map that will show you how many affordable units in each county for 100 poor households, click here. In Vermont, Orange, Windsor and Windham counties come out the best, with 49 affordable units for 100 households; Caledonia, Lamoille and Orleans have the fewest, at 29. The national average: 28.

Of course, the national challenge is not just to create plenty more affordable housing but to locate it judiciously. New housing options have to be provided for low-income people in low-poverty neighborhoods, otherwise known as “high-opportunity” areas. That’s what affirmatively furthering fair housing is about — breaking up historic settlement patterns of concentrated poverty and segregation and promoting integration.

Naturally, AFFH generates pushback. So, sprinkled among the wash of “housing crisis” stories are accounts of resistance to affordable housing projects in well-healed suburbs – such as Simsbury, Conn. (median household income$104,000) , and Wilmette, Ill. ($127,000).