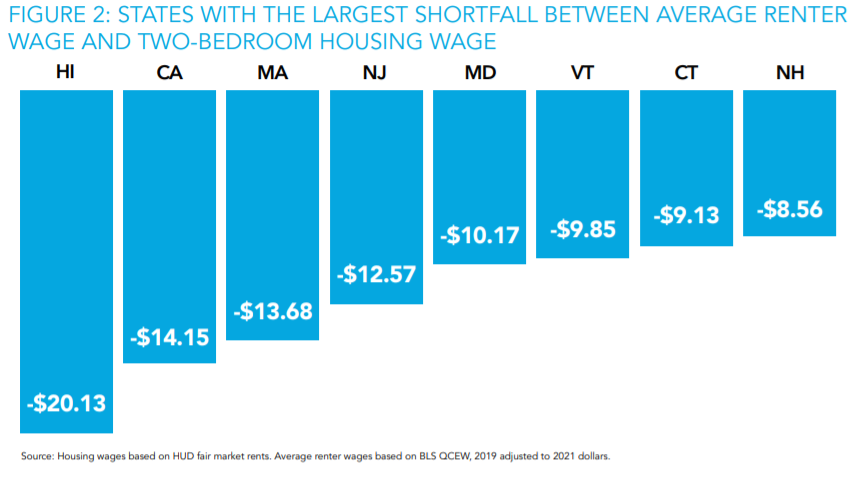

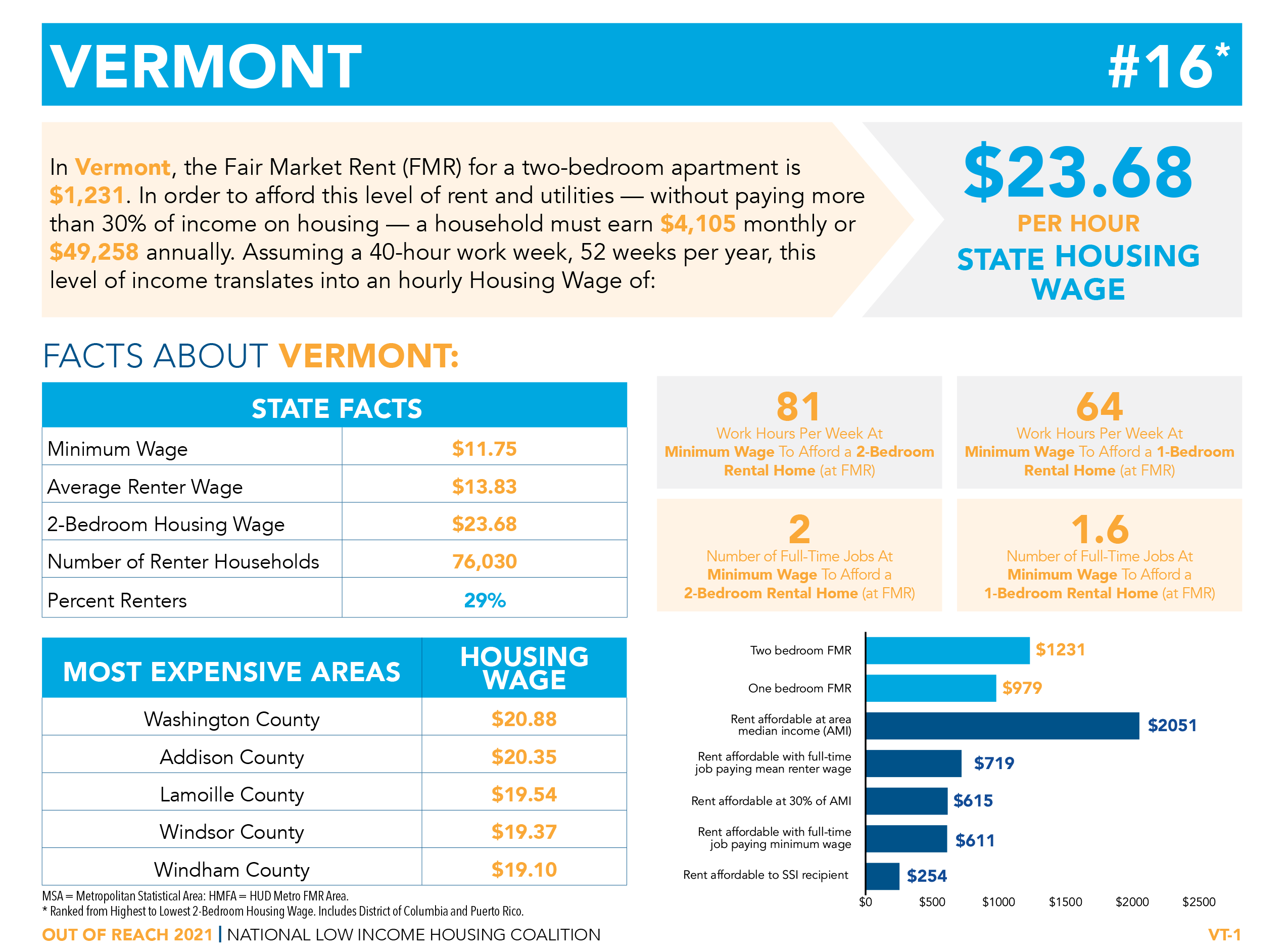

The recent release of the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s Out of Reach report shows that Vermont has the sixth largest shortfall between the average renter wage and the two-bedroom housing wage. In the Burlington/ South Burlington region, where the 2-bedroom housing wage jumps from the state’s average of $23.68 to $31.31, the housing wage gap is particularly acute. This means that full-time employees living in Burlington and South Burlington have to make $31.31per hour in order not to spend more than 30% of their income on rent. Meanwhile, the average hourly wage for Vermont renters is $13.83.

“We’ve been in the midst of a chronic affordable housing crisis for many, many years,” Kerrie Lohr of Lamoille Housing Partnership, asserted to VTDigger earlier this week, “This report pretty much shows what we already know to be true, is that housing is out of reach for many of Vermont’s renters.” What housing advocates have been seeking to address over the course of Vermont’s long housing affordability history crisis has become especially acute during this past year. While Vermont’s housing sales spiked 38% this past year, many of these new residents purchased with cash-on-hand, often significantly over the asking price, with sales of million dollar homes almost tripling.

These numbers are particularly concerning when we turn an eye to Vermont’s pattern of racial inequity. This year saw rates of COVID doubling in communities of color, highlighting the disparities in health and economic opportunities for People of Color in Vermont. Nationally, the home ownership rate of White households is 70% to the 41% of Back homeowners, a gap caused and reinforced by a pervasive history of racist housing policies, inequal lending, and lack of meaningful policy change to address this systemic problem. Vermont’s homeownership gap is much larger with only 21% of Black households owning their home compared to 72% of white households. Local student activist (and current Fair Housing Project intern) Minelle Sarfo-Adu spoke to VPR about experiencing this stark disparity in her South Burlington community, “I think I only have two African American friends in the whole — like in all Vermont, that actually own homes,” she said. “Other than that, every other one of my friends actually rents, unless they’re white. All my white friends actually own their homes.”

The severe affordability crisis in Vermont creates an environment where landlords can be more discriminative in who they rent to. For renters who belong to the Fair Housing protected classes and face the greatest barriers to housing access in our state, this means longer and more desperate housing searches. While housing advocates are certain that most discrimination goes unreported, testing performed by the Housing Discrimination Law Project of Vermont Legal Aid indicates that housing providers generally disfavor African American renters, renters of foreign origin, renters with children and renters with disabilities. Reports from the CVOEO Vermont Tenants hotline and housing community forums are riddled with stories of people being turned away from housing because of a housing voucher or for having children (both violations of the Fair Housing Act in Vermont), and of desperate housing decisions such as signing leases before viewing the property or even offering to pay more than the listed monthly rent.

So what do we do about it?

“Treat the housing emergency like an emergency,” retorts the collective voice of Anne N. Sosin, Mairead O’Reilly, and Maryellen Griffin in their recent VTDigger commentary, “Housing is a Public Health Crisis in Vermont.” Sosin is a policy fellow at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College; O’Reilly is a medical legal partnership attorney at Vermont Legal Aid; and Griffin is a housing attorney at Vermont Legal Aid. Housing activists, policy makers, and the broader population of Vermont need to act now to address this growing problem, they wrote as they shared the major lessons housing advocates have gleaned from this past year of COVID response. Their voice has urgency, as some key opportunities to enhance renter protections have already passed. These key missed advocacy moments include the veto of the Rental Housing Safety Bill and a failure to delay the ending of the State of Emergency – which had expanded shelter space for houseless folks through federal CARES funding – until more rental housing was made available. Some economists and sustainable communities experts caution this trend is only at its early fruition as climate change pushes folks from more geographically vulnerable locations.

Much of what Sosin, O’Reilly, and Griffin called for is still possible. “Mobilize a statewide response,” they stated, noting that these solutions will be unique to the region and therefore require regional solutions. Our Fair Housing Friday panelists this spring noted that creative solutions require broad civic engagement, especially from those most impacted by the growing inequity of available resources. Housing Committees are a critical tool to mobilizing regional solutions to a statewide problem and can jumpstart conversations at the community level. The common thread running through all these solutions is that they must center the needs of the communities consistently facing the highest barriers to housing.

This is a market failure and we need to treat it as such. At $300-325 a square foot no amount of tax incentives and credits are going to get for profit projects to “pencil out”. Money needs to go into the housing trusts for new construction.